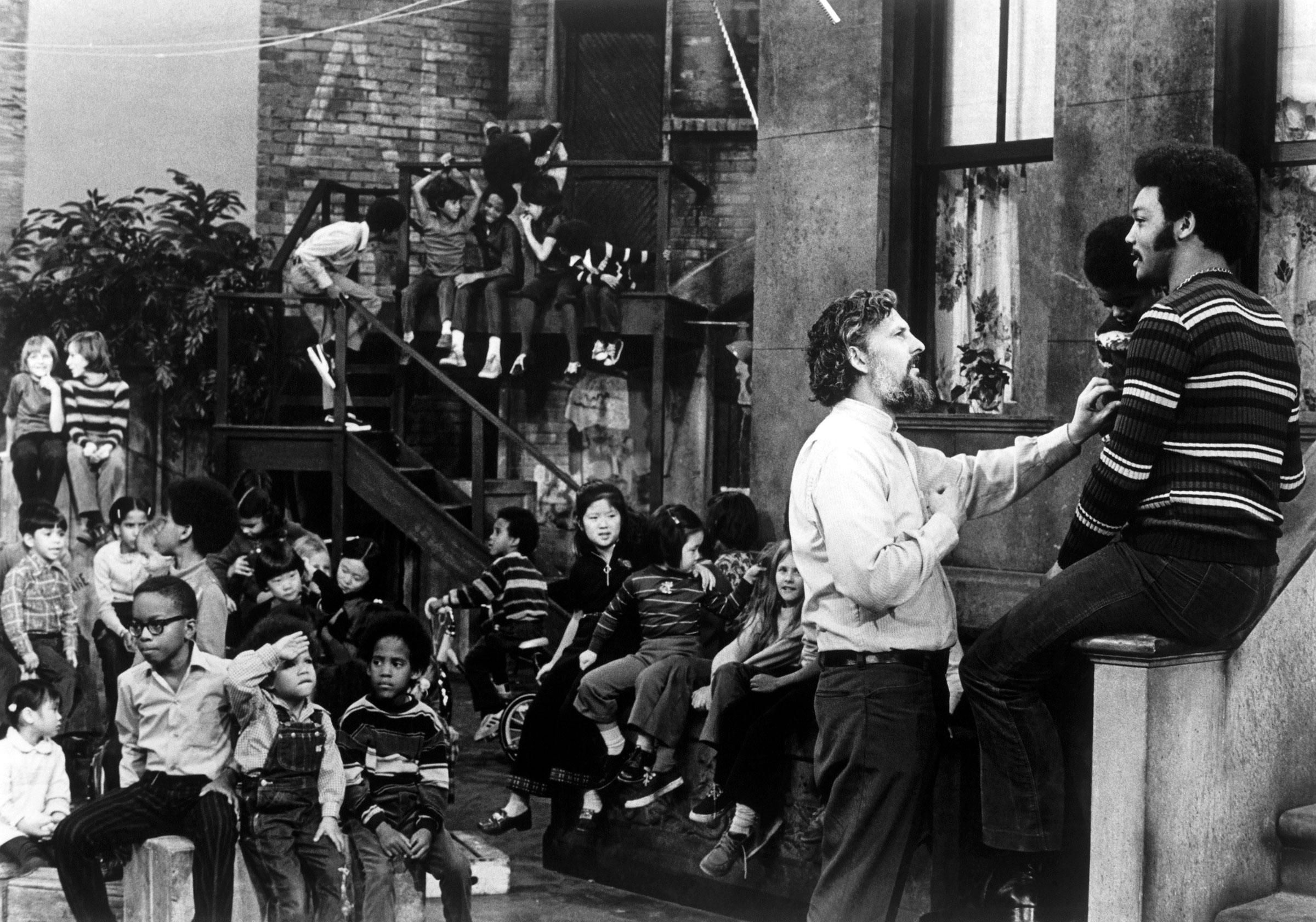

Jesse Jackson sat on what looked like a brownstone stoop.

“You ready…?” he asked.

“Yeah,” said a chorus of little voices, small children with little attention spans seated on the concrete-covered ground, the steps of fire escapes, and other features of what television producers imagined filled out an ungentrified 1970s city landscape.

“OK. Here we go. I am–somebody,” Jackson says before prompting the children to repeat after him, phrase by phrase, as if learning a mantra. In reality it was the language of a poem, written decades earlier by the Rev. William Holmes Borders Sr., an Atlanta pastor and civil rights activist who beginning in the 1940s had illuminated on his radio program the truth about American segregation and inspired, among other listeners, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. But it was in many ways Jackson, an activist and King acolyte, who was with King when he was assassinated in Memphis, who had made the poem famous, reciting it, whole or in parts, in many of his public speeches since King’s murder, even recording it on an album. “I am –somebody. I may be poor. But I am–somebody.”

It was 1971 and Sesame Street, a three-year-old mission- and research-driven public-television show, was already a bona fide cultural phenomenon, a kind of mirror of what was new or meaningful in the culture. And at least a part of what had drawn America’s attention to Jackson was the often evocative, sometimes rhyming, almost always memorable way he spoke about the contrast between America’s promise and its reality. Jackson, it was already clear, was arguably one of America’s greatest living orators, cognizant of the significance of the sound bite and the soliloquy. But that’s the kind of thing the world will have to take in now largely from bits posted online or memorialized on tape and film.

In 2017, Jackson announced he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, a brain disorder that can cause uncontrollable movements, stiffness, and challenges with balance, coordination, mobility, and speech. Late last year, Jackson announced plans to step down from the helm of Rainbow PUSH, the Chicago-based civil rights organization he founded in 1996. This weekend, Jackson publicly named his successor, the Rev. Frederick Haynes III, at the Rainbow PUSH Coalition’s annual convention in Chicago.

Jackson, now 81, spoke less precisely, far more slowly, and with less gusto than the young man who once sat on that stoop. He announced plans to “pivot” rather than retire. “I struggle to speak,” Jackson told me during a late Friday interview. “But I can still think. I can still write. There is still work that I want to do, work I intend to do.”

Haynes, 62, is the senior pastor of Dallas’ Friendship-West Baptist Church, a 12,000-member megachurch he grew from 2,000 members beginning more than four decades ago as a young man, drawn into Jackson’s orbit by the power of his speech. He will continue to serve in that role when he takes the helm of Rainbow PUSH in the coming weeks.

“I have determined that I am not going to try to stand in his shoes,” Haynes tells me. “I’m going to try to stand on his shoulders. It’s hard to imagine anyone being as oratorically gifted as Jesse Jackson, being able to use a few terms to convey monumental truths. I mean no one has ever done it better. When he says ‘keep hope alive,’ when he says ‘not charity but parity,’ those are phrases that are short and yet they are loaded with such significance you could almost make a book of what I call Jesse Jackson proverbs.”

It’s not just Jackson’s words, but how Jackson in his heyday delivered them

“‘I Am – Somebody’ sends chills down the spine,” says Andre Perry, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., about one of Jackson’s many recitations before adult audiences who also repeated the poem’s words. “You don’t know if he’s saying it as a demonstration or saying it as a mantra for the country, for Black Americans to realize their own power. It was and is, like wow. It’s just amazing, an amazing use and delivery of language. I tell people all the time, you can say what you want about Jesse Jackson, but ‘I Am–Somebody,’ you need to play that at least twice a year to get your mind right.”

Perry, who researches and writes about the ways policies and practices sustain racial inequality in the United States, was raised in Louisiana, mostly by older Black women who regarded Jackson, a son of Mississippi, as the young lion of the civil rights movement – the handsome, church-raised, college-educated man who could dance. Jackson knew how to speak, how to hold those with power to account, he was a man of God, Perry says, but “when he spoke, he was a man of the people.”

So much of Jackson’s charisma was always tied to the way he spoke, the way he delivered ideas, Perry says. He inspired millions through words and actions, saying and then actively doing things to challenge both the Black and the white establishment.

“I could make the argument that post-civil rights era he is the most consequential African American leader,” says Cornell Belcher, president and founder of Brilliant Corners Research and Strategies. In 2005 Belcher became the first person of color to serve as the chief pollster for either of the United States’ major political parties and a few years later the primary pollster and a political strategist for the groundbreaking 2008 campaign of Barack Obama. “And what do I mean by that? Barack Obama wasn’t an African American leader, he was an African American who was a leader. But he doesn’t get to be an African American who was a leader without an African American leader opening up that doorway or the possibility of it.”

Hearing Jackson speak on TV during his senior year of high school changed the course of Belcher’s life.

“I literally registered to vote because of Jesse Jackson,” Belcher says. “I didn’t come from a political family. My father was a cement finisher. My mother was a factory worker. We didn’t talk about politics at our table. That wasn’t a topic over the holidays. But Jesse Jackson captured and won the hearts and minds of a lot of young people like me. On a personal level, I can connect the dots from where I am today back to Jackson’s movement.”

In 1984, when Jackson first declared himself a candidate for President at a Philadelphia church, he laid out a vision for vast political change if people of color and young people of all races realized and combined their political power. Jackson insisted it was not only rational to focus the nation on hope, peace, and investment in human beings rather than weapons, it was essential. As Belcher wrote in his 2016 book, A Black Man in the White House: Barack Obama and the Triggering of America’s Racial-Aversion Crisis, “Jackson said, ‘Reagan won Massachusetts by 2,500 votes. There were over 100,000 students unregistered, over 50,000 Blacks, over 50,000 Hispanics … Rocks just laying around.’ The strategic brilliance of the Obama campaign was, [that] we decided to pick up the rocks.”

Though Jackson never became the nominee, out of his 1984 and 1988 campaigns also emerged a group of Black women political insiders Belcher sometimes refer to as “The Colored Girls,” a reference to a book some of them published in 2018, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Politics. That group includes Donna Brazile, Yolanda Caraway, the Rev. Leah Daughtry, and Minyon Moore, women who have held high-level positions inside the White House, the Democratic Party, and multiple presidential campaigns since the 1980s.

“There is a legacy of political leaders and operators in progressive politics today that are part of Jesse Jackson’s tree,” Belcher says, “that are flowers on that Jackson tree. Go look at what the DNC was before 1984. It was a lily-white power structure.”

In 1989, Ron Brown, a Jackson aide, was elected the Democratic Party’s chairman, the first Black person to lead a major U.S. political party. The year before that, Brown had spearheaded a Jackson project to transform key party rules related to the process that produces a White House nominee. Jackson’s performance in the 1988 Democratic Party primaries and his crowd-stirring “Keep Hope Alive” speech at the party’s convention gave him the leverage to end the winner-takes-all primary system. Jackson, who in 1984 had become the first Black person to win a major U.S. party’s state primary and in 1988 won 10 primaries as well as three caucuses, demanded a proportional system, meaning that candidates were awarded a number of delegates in proportion with the votes collected in primary states. This gave people of color and issues that may be of particular concern to them a larger voice in the process to determine the party’s nominee. This also makes it harder, but certainly not impossible, for frontrunners, like Hillary Clinton in 2008, to push challengers, like Obama, out of a presidential race early.

After his presidential campaigns, Jackson, long interested in household-level and national economic patterns, pivoted toward work on what he called “silver rights,” redressing the ways that Black Americans were routinely locked out of certain high-paying or influential jobs, many loans, most boards and corporate leadership roles, and public contracts, and in the process economically pinned in and rendered vulnerable to financial predators or left with only bad options.

“I was at that time a young man trying to find my way, what I wanted to do with my life and especially in ministry,” Haynes says about the first time he heard Jackson speak at his Texas college. “I was studying Martin Luther King Jr., his life and work, and he [Jackson] comes to campus. And he is of course not only a protege of Dr. King but for me, in the 80s, doing the kind of ministry and work that continued the prophetic ministry and social-justice activism of Dr. King. So immediately I am struck by this amazing figure with charisma and ability to enrapture an audience.”

Haynes even has specific memories of what Jackson said.

“He used the metaphor of a symphony having movements,” Haynes explains. “And he said the last movement would be having access to capital and it just made sense to me because he talked about our freedom symphony – emancipation from slavery, the civil rights bill, which was integration into America or access to public accommodations, as he would say, and then there was the voting-rights bill. The last movement is access to capital. So he’d often use the phrase, ‘We have to move from pursuing our civil rights to pursuing our silver rights.’”

This particularly overt demand for access to some of the levers by which other Americans have amassed wealth or at least reduced financial vulnerability seemed to engender a new set of critiques. Jackson and others were sometimes characterized as men exploiting the poor or those visited by the tragedies racism can produce for media attention and free airtime, wielding the threat of negative publicity for material gain in the form of donations to nonprofits and initiatives. But some may have forgotten – or willfully disregarded – the fact that among King’s primary concerns, clear in the content of his final speech and book, was the fight for economic justice, Haynes says.

“No one, as far as I am concerned, embodied that, took that mantle, and ran with it like Rev. Jesse Jackson and the struggle for silver rights,” Haynes says.

Perry, who wrote the 2020 book, Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities, says Jackson’s phrasing about Black America’s economic condition is so potent that what Jackson and others were demanding – structural change, policy changes shaping markets – has in some minds melded with a singular focus on individual capitalist pursuits.

“For a lot of people, any delving into capitalism is essentially civil rights and social justice,” Perry says. “Clearly social justice should include economic issues and markets, because they are broken. Many, like Jesse Jackson, want to change markets but not everyone absorbed all of that. I think today we know how hard it is to talk about participation and structural change at the same time.”

More recently, pastors have lost some of their influence with much of the American public, including Black America. The idea of a leader who shows up in crisis is anachronistic and suspect to many people. People are, however, interested in and drawn to wealth, view it as a signifier of wisdom, and are perhaps a little less interested in the communal uplift that’s at the core of Jackson’s life’s work, Perry says. It’s why you see prominent individuals, Black and white, speak about pursuits in business like they are collective gains, use social justice as marketing, or deride politics and protest as insignificant, despite doing little to change the rules so that other people on the outside can get in.

In 2014, Jackson went to Ferguson during sustained protests following the killing of Michael Brown by a police officer. He was booed by protesters, many of them Black, a painful sight for Perry.

“Jackson, I will say this about him,” Perry says. “He was truly about doing things, about being realistic about where we are as a people. He was trying to radically change the policy framework we are in and the markets that we participate in. So I just always have a hard time when people knock Jesse Jackson. Yes, he has some personal issues. He has a couple of things, in his life, that have not been ideal. But he did navigate some complexity that, on others, seems lost? Yes.”

The last time I heard Jackson speak at length, it was in a Minneapolis hotel ballroom where many of George Floyd’s family members had gathered to watch a private, closed-circuit feed from the courtroom where a judge would read the verdict in the case against Derek Chauvin. After Chauvin’s conviction, one that statistically speaking was unlikely, Jackson seemed stunned. An aide eventually helped him into a chair. Jackson, speaking barely loud enough for me to hear, told me how significant this moment was in a country that had allowed lynching as a kind of pastime and left all manner of massive injustices unaddressed. He mentioned the perverse way that the suffering and death of Black Americans has repeatedly been a catalyst for change in this country. Emmett Till. Rosa Parks, who said she thought of Till when she refused to leave her seat and had spent previous years investigating the unpunished sexual assaults of Black women by white men. King, who the night before his murder, seemed to know the end was near. And now Floyd. He wondered if America’s sudden zeal for self-examination and improvement would last or produce what it had so often in the past: backlash.

I had to sit close and lean in closer to hear him, to make out his precise words. His comments, his questions were prescient. I had seen him the previous year in Kenosha, Wisc., after police shot and paralyzed a Black man. There he’d needed help stepping off a curb, getting in and out of an SUV. But Jackson’s condition, it was clear, had worsened.

When we spoke on Friday, more than two years after that April day in Minneapolis, he said pinning some of his hopes on technology to make his plans possible. He wants to work on negotiating the release of Americans held abroad, something he has done before. He plans to spend more time thinking and writing on the complex realities that define this period. He wants to teach seminary students, focusing on the religious rationale for social justice and the tactics of civil rights activism. And with a Supreme Court uninterested in expanding or protecting rights and in the absence of tools like affirmative action, he wants to help people to identify ways to use their leverage to secure better conditions.

When I ask him for an example, Jackson, who attended college on a football scholarship and rejected an offer to play minor-league baseball, tells me he believes that Black athletes schools want to recruit to play for their multimillion-dollar programs should begin asking for overall student-enrollment and graduation demographics. Then they should consider only programs with reasonable and growing numbers.

“There is always leverage,” Jackson says. “It is a matter of recognizing it, realizing it, and using it really and truly for the greater good.”

The alliteration, the penchant for articulating ideas in a way that is easy to follow is still there.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at [email protected]