In 2006, Corey Matthews was the first person in his family to go to college.

The application and selection process was so foreign to him that community programs that illuminated his options and helped him apply to several schools were a godsend. But when he had to decide where to actually enroll, Matthews merged what he had been taught with a criteria straight out of the movies.

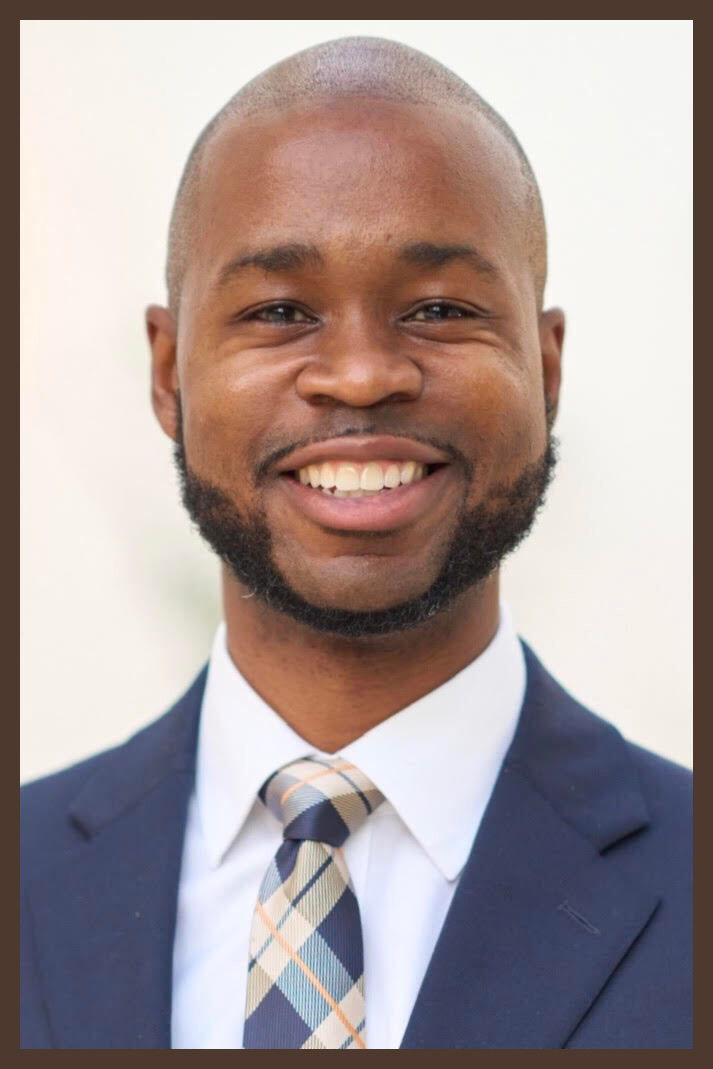

“I grew up in L.A. so I associate UCLA with sports, which I didn’t really have an interest in, but I did have an interest in big parties,” says Matthews, now 34 and a vice president of global philanthropy with JP Morgan Chase. Today, he helps to manage a grant portfolio in Los Angeles consistent with the company’s goals, the kind of multifactor strategy work that makes him chuckle about his 17-year-old logic and sigh when he thinks about just how significant that decision and, in many ways, his freshman class became.

What Matthew found on campus was something far different than a series of ragers interrupted by classes and coursework. In 2006, 10 years after California voters first banned race consideration in college admissions with Proposition 209, just 96 Black freshmen were admitted to UCLA, one of the state’s two flagship public universities. After a few more students were admitted during the appeals process, Matthews ultimately became one of just 100 Black freshmen out of 4,852 total. But the initial news of 96 Black students – a figure unseen at one of California’s most prestigious public universities since the early 1970s – situated a respected institution in one of America’s most diverse cities and a state often understood as a caricature land controlled by progressive policy and people as the place to watch for those on both sides of the affirmative-action debate. California had become the first state in the nation to ban affirmative action in admissions, to lean into a particular conception of American fairness and absolute meritocracy that those opposed to affirmative action say exists.

Of course California has long been more complicated than those who consider the Golden State a byword for progressive excesses and accommodations. Its voters, after all, have sent Ronald Reagan, Dianne Feinstein, Maxine Waters, and Kevin McCarthy to Washington. Nearly 55% approved Proposition 209. And it has long been a kind of laboratory where new and sometimes long-sought-after policies get implemented and their effects often become clear.

When California eliminated affirmative action in college admissions, Black and Latino student enrollment in the University of California system declined, with the sharpest drops happening at the state’s flagship universities. A fraught, sometimes taxing on-campus atmosphere developed for the small number of Black and Latino students who did enroll, but it also breathed new life into a rich tradition of student activism. The change pulled students, alumni, and some faculty into a range of efforts to recruit, admit, and retain a larger number of Black and Latino students, producing notable but modest effects which, after the nadir of Black student enrollment became the subject of national headlines in 2006, slowly pushed back against the creep of Proposition 209-inspired thinking and practices at the states’ public colleges and universities.

More from TIME

But by 2016, two decades after California voters approved Proposition 209 and a decade after the push to counter its effects gained force, something else was also clear. Student enrollment in the University of California system, one of the most well-regarded in the nation (it includes seven schools considered so-called public Ivies) still didn’t look much like the people who live in the state. Black, Latino, Native American, and Pacific Islander students made up about 56% of the state’s high school graduates but just 37% of those enrolled in California’s public colleges and universities, University of California data indicates.

Read More: What Killing Affirmative Action Means for the American Workplace

In the years since Proposition 209, at least 10 other states have gone the way of California, banning affirmative action in college admissions with two reversing course after courts struck down those policies. But now that the Supreme Court has ruled that race-conscious affirmative action in college admissions at both private and public universities is unconstitutional, the whole country will join them. And for a large segment of the population, that’s just fine – according to a recent Pew Research Center poll, only 33% approve of selective colleges considering race and ethnicity in admissions decisions.

“It’s interesting, the national discourse around affirmative action at the time,” Matthews says about his experiences at UCLA beginning in 2006, “it felt very clear. If you believed in social justice and understood equity and race — and we weren’t even using terms like equity – you would be OK with affirmative action, almost immediately. But affirmative action has evolved to something completely different. People will say, ‘Yeah, I believe in equity, but is affirmative action the way? Oh, I don’t support that.’”

The lessons of what happened in California are important to understand.

Back in 2006, it didn’t take long for Matthews to realize that what he’d hoped would be a fun school right there in his big-city hometown was also a swirling vortex of controversy.

“There was just a lot of outcry around how there were not even 100 Black students out of an entering class of 4,000. Then you peel that back a little bit further and there were even fewer Black men, young Black men coming into the university.”

What that ultimately set in motion for Matthews is something he’s still unpacking today.

“UCLA is not bashful about its student activism, taking very public stances on certain issues, having students agitate on certain issues,” says Matthews. “Because of that…when I got there, I always say the campus sort of descended upon me.”

It’s hard for him to remember now, but he thinks it was at events set up by the UCLA Afrikan Student Union for the incoming freshmen class in April of his senior year in high school that he learned how Black student enrollment, what people were already calling “the Infamous 96,” compared to previous years. A few months later, Matthews was on campus, a freshman, navigating his first steps into adulthood. On the first day of class, he was approached by a Black upperclassman with one of those “are you with us?” kind of conundrums.

“[He] came up to me and said, ‘Come with me and go to this protest,’” Matthews says.

Matthews felt torn. He knew he needed to go to class but also that the work of trying to raise questions and find solutions to the dearth of diversity on campus was very important.

He went to the protest, then to his later classes. But the people he connected with at that protest, the work he did with them, the work he did helping to recruit Black applicants in Los Angeles, and the work he did as the eventual Afrikan Student Union chairperson in coalition with Asian and Latino student groups familiarized him with a concept that is much talked about in college-admissions circles today.

Read More: Read Justice Sotomayor and Jackson’s Dissents in Affirmative Action Case

The concept is called holistic admissions. It requires or calls on schools to consider more than a student’s grades and ACT and SAT scores. Research has shown that these standardized tests do not accurately predict college performance but closely reflect the education and wealth of a student’s parents and a student’s access to test-prep tools. And an admissions system that depends on them alone disadvantages Black and Latino students, those who come from poor families, and those who are among the first in their families to go to college or trying to navigate the higher-ed system without some kind of experience or guide. Holistic admissions require a school to consider academic performance but also who a student is, what they have tried to learn or do inside and outside of school, what they have had to manage or opted to take on, the context in which they grew up, what interests and hobbies they have developed, how they have contributed to their communities and what all of this together suggests about a student’s potential to contribute to campus life and to the communities where they live after graduation. The concept came up during oral arguments at the Supreme Court last year, with Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson probing why, if a university is evaluating an applicant holistically, race should not be considered while other factors, such as a family’s history with the school, could. “That seems to me to have the potential of causing more of an equal protection problem than it’s actually solving,” she said.

Holistic admissions acknowledge that there are multiple types of promise, intelligence, and ability, says Mandela Kayise, who in 2006 was the president of UCLA’s Black alumni association. He had arrived on campus as an undergraduate student in the late 1970s only to be forced out by economic challenges, returned in the 1980s to finish his degree, and joined the administration working in student advising and retention. Kayise also served as a faculty advisor to student groups when Prop 209 passed in 1996 and was doing similar work 10 years later when the Infamous 96 arrived. There were protests against Proposition 209 before and after it passed, he says. But it was when the Infamous 96 got there, human proof of exactly what the ban’s opponents had warned would happen, more of the campus, people connected to it, and Los Angeles civil rights organizations got involved. “It became ‘enough is enough,’” says Kayise, who is now the president and CEO of New World Education, a college-access, student-retention and leadership-development organization. For the Infamous 96, and some alumni, holistic admissions became a major focus of student activism and ultimately, a practice UCLA implemented in 2007 and the entire University of California system would follow in 2020.

In 2006, Peter Taylor, a Black UCLA alumni, became chair of the university’s task force on African American student recruitment, retention, and graduation. It included students, administrators, faculty, staff, and members of the municipal community. “One of the things we looked at was why UCLA’s African American [student] population had been shrinking,” says Taylor, a now retired investment banker who has also served as president of the UCLA board of directors, chair of the UCLA foundation board, and spent five years as the University of California system’s chief financial officer. At the time, the system consisted of 10 campuses and five medical centers with a $24 billion budget. “Prop. 209 was a big part of it, but part of it was that the admissions system needed to be transformed, a chance for students to make a holistic case for themselves. And we also raised a lot of money for African American students.”

Black student enrollment slowly began to grow again. Taylor knows that some people will say, “Oh, well, you were just giving them such great scholarships that of course they decided on UCLA,” or presume that race-based scholarships violate the law. But while the University of California could not operate a race-based scholarship, community foundations could and did. And, in most cases, the community-foundation scholarships amounted to a letter to Black students who had been admitted saying, “Congratulations and here is $1,000 to use toward your college costs.” It wasn’t much compared to the cost of college, but $1,000 can make a difference for very low-income students who often face transportation challenges, relatively small costs that they simply can’t cover for a textbook, or issues balancing work hours and school. Plus, the letters included the names of established professionals who were Black alumni.

Read More: The Ambitions of the Civil Rights Movement Went Far Beyond Affirmative Action

The school’s admissions officers also fanned out and engaged in more on-the-ground, in-person recruiting activity. Under the old way of operating, simple, relatively low-cost, human-to-human niceties like this didn’t happen often, Taylor says.

Still, by 2020, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, had found that the end of affirmative action in public college admissions had not only reduced overall Black and Latino student enrollment at California’s public universities but also done damage to these students’ college-graduation rates and wages earned after the college years. What’s more, the 2020 study, released by Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education, found that claims that affirmative action in college admissions had harmed white and Asian students did not bear out when researchers examined enrollment, graduation rates, and earnings before and after Proposition 209. Instead, the ban on affirmative action in college admissions had contributed to a sort of two-tier higher-education system where the state’s flagship schools – UCLA and Berkeley – are attended overwhelmingly by white and Asian students while the other schools in the system, many of which had low Black and Latino student enrollment before the change, saw some gains. Proposition 209 also deterred thousands of qualified students from these same groups from applying to any campus. Because fewer students of color enrolled in UC schools overall after Proposition 209 and the number enrolled in STEM programs, particularly among Latino students, also fell, the number of early-career Black, Latino, Native American, and Pacific Islander graduates earning over $100,000 dropped by at least 3%. The study provided the “first causal evidence that banning affirmative action exacerbates socioeconomic inequities.”

That year the system’s board of regents voted unanimously to support a repeal of Proposition 209. They also agreed to phase out requirements that applicants submit SAT and ACT scores, then by 2025 develop the system’s own standardized test. The state’s lawmakers put the question of repealing Proposition 209 on the November 2020 ballot. But California voters defeated it – with 57% voting to keep the ban on affirmative action in college admissions in place.

Beyond the enrollment figures and the graduation rates, there are the experiences of being a Black human being on a campus like UCLA’s. And to this day Kayise wonders if the Infamous 96 were a class asked to take on too much.

“They were so small,” he says. “They not only had to figure out how to thrive themselves in an environment where there were fewer of them to provide support to one another but they picked up the job of trying to help the next generation of high school students gain access and rebuild some of the programs and community-service projects, the [Black] fraternities and sororities that were suffering.”

In essence, as Black student enrollment slid to that low in 2006, some of the organizations, events, programs, and infrastructure that previous groups of Black students could rely upon for social, emotional, and academic support had shriveled or died. The Infamous 96 had to rebuild them and use them at the same time.

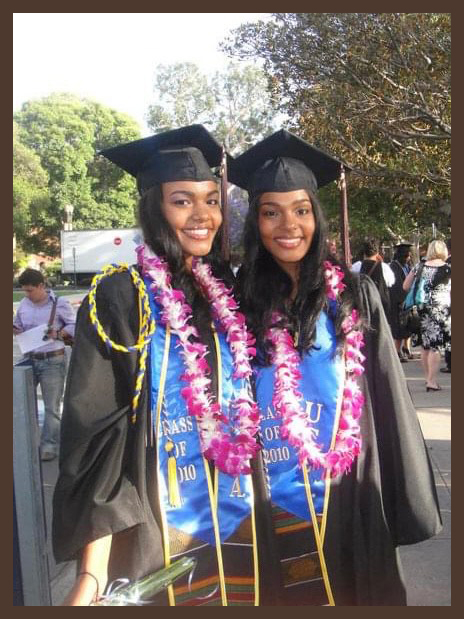

“Going to college is hard, it’s hard enough,” says Rachel Aladdin, another member of the Infamous 96. Like Matthews, she was a first-generation college student. She grew up in Pasadena, about 30 miles and an entire world northeast of UCLA’s campus outside Los Angeles. Aladdin and her identical twin sister, Rebekah, were raised by a single father, who was living with multiple sclerosis. So as they applied to college, they considered practical things, like the ease with which they could get back to Pasadena on the weekends.

Rebekah received an admissions letter from UCLA first. Rachel doesn’t think hers ever came, but she found out that she too had been admitted five stressful days later when a high school history teacher let her log into an admissions website in his classroom.

Rachel Aladdin was awarded a four-year scholarship from the Jackie Robinson Foundation, and by that summer she was on campus for the freshman summer program, an academic enrichment and social-adjustment program for students coming from underserved communities. Between that and freshman orientation, she thinks she met all of the Infamous 96. There were a number of athletes among them including the NBA player Russell Westbrook. The 96, and for that matter the limited number of Black students on campus, were generally close, and from this Aladdin drew a big circle of friends. It was, perhaps, the one upside of such a small group of Black freshmen. She grew up in a family where race was talked about, and while her hometown was diverse, there’s a fair bit of effective segregation, she says. So, being one of just 96 Black students admitted was upsetting but not surprising. What was hard was the day to day on campus once classes began.

Read More: The Supreme Court’s Decision on Affirmative Action Must Not Be the Final Word

“When you have the troubles of life on top of that, as a Black person from an underserved community,” Aladdin says, “and you now have this racial climate that you have been thrown into. It was crazy. I don’t know if some of my experience was projection because it was so top of mind. There are 96 Black freshmen here. And you felt alienated. You felt very different.”

When Matthews arrived on campus, he was, as he puts it, all of 5 ft. 3 in. Yet, non-Black people all over campus frequently asked him questions or mentioned things to him that seemed to hinge on the presumption that he was an athlete.

“I’ve since had a little growth spurt so I am now 5 ft. 7 in.,” he says. “But what I could not believe is that people, at this Division I school, seriously looked at me and made their assumptions. This was before we had or at least I knew of terms like microaggressions, pre-DEI and all of that.”

It often made Matthews, other members of the 96, and other Black students on campus feel as if they weren’t welcome.

“We really started talking about campus climate and safety and feeling psychologically safe and feeling that, ‘Do I belong here?’ thing,” Matthews says. “This was about like look, I’m on campus. I stick out like a sore thumb. I stay in my little small enclave and I go to class and that’s what I’m doing.”

Matthews didn’t feel welcome so he didn’t engage in many parts of campus life. He got in. He did what he could to make way for others. He went to class. He learned. He graduated. He got out. He’s accepted that not everyone actually grasps the difference between equality and actual equity, that people are sometimes rude intentionally and sometimes don’t know exactly how offensive they are. Sometimes they simply do not care.

For Aladdin, the climate on campus made her question everything. When someone would fail to move over to share the sidewalk, forcing her into the grass, she often wasn’t sure if they were just rude or they were racist. When someone failed to hold a building door despite her trailing only inches behind, when people didn’t thank her for holding the door for them or making room for them on a bench, she wasn’t sure.

Read More: How the End of Affirmative Action Could Affect the College Admissions Process

“You often found yourself asking, how racist is this, really?” Aladdin says. “I think with time those thoughts subsided, but at first…I made sure I was aware of my surroundings because I didn’t know how weird things could get.”

When she walked across campus or anywhere near the row of white fraternity houses, she felt particularly anxious about her safety. It wasn’t that she thought white frat guys were particularly dangerous. It was that she wasn’t sure anyone would care or respond if she became the victim of a crime and she worried about hate crime specifically. In class she was often the only Black person in the room and felt the need to represent Black people well. But unlike her classmates, most of whom had laptops and in some cases, multiple devices, she and her sister were sharing a desktop. She majored in world arts and cultures and found other students in the department, many of them wealthy and most of them white, a bit standoffish.

Aladdin, who since graduation has worked as an actress, model, songwriter, and screenwriter, has an ad-sales job at Disney and a BET Christmas movie on her resume, Merry Switchmas, featuring both her and her twin. But when she was a freshman, she had to deal with all of that on top of all the other changes that come with anyone’s adjustment to college.

“The emotional gymnastics of having to analyze it,” says Aladdin, who went home every weekend until her father died her senior year. “You have this dynamic that felt so uncomfortable, but then you also felt this responsibility to do something about it.”

In the fall of 2021, UCLA championed the demographics of its new student body. It had required a lot of effort and spending on targeted recruitment and other activities that began after the year that brought in the Infamous 96. It still wasn’t much like the state’s population but had restored and surpassed the level of campus diversity in 1995 the year before Proposition 209 passed. In 1995 there were 790 Latino students on campus. In 2021 there were 1,185, according to the school’s data. There were 259 Black students enrolled at UCLA in 1995 and in 2021, 346. (Federal data puts percentages for Black and Latino students that year slightly lower than UCLA’s figures.) But even the University of California system itself argued last year that the loss of affirmative action had had a profound impact, writing in a brief to the Supreme Court that “[f]or nearly a quarter century, UC has made persistent, intensive efforts to improve the diversity of its student body through race-neutral programs, yet full realization of the educational benefits of diversity remains elusive.”

A public university system exists to educate, to prepare, to enable the intellectual and economic growth of a state, its people and the country around them. It exists to foster the development of leaders and innovations and meet social and economic needs. So, Taylor has also grown concerned about other after-effects of Proposition 209 and some phenomena which predate it but have grown more intense. Away from the California flagships, Black and Latino student enrollment has slowly climbed on campuses where these students were once scarce. He worries that public resources aren’t keeping pace. That’s true in other parts of the U.S. as well, where most students, and certainly the vast majority of students of color, attend open or nearly open enrollment schools as opposed to the elite institutions at the center of the affirmative-action debate. There, public funding cuts have shifted more costs onto students, including many low-income students.

UCLA, like every campus, always had people occupying every place on the continuum from anti-racist to open bigot, Kayise says. It always had people who hated affirmative action and took every chance they could get to “accuse” Black students of “taking” someone else’s slot. Both Matthews and Aladdin had a version of that very exchange, a decade after the affirmative-action ban. Kayise recalls a professor who kept a cartoon affixed to his office door that read “Affirmative Action lets them in. I kick them out.” So Kayise has a warning to a country that just followed California and banned race-based affirmative action: Watch the campus climate, the way all students are treated.

“People need to be prepared,” Kayise says, “for the kind of attitudinal change that you might find. People who maybe feel like Black people don’t belong on those campuses may now feel emboldened. They may no longer feel an obligation to lift a finger to facilitate any form of diversity, no need to diversify the staff, try to bring new voices onto the faculty. Like, you are free now to say what you feel.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at [email protected]