These are independent reviews of the products mentioned, but TIME receives a commission when purchases are made through affiliate links at no additional cost to the purchaser.

The moment Rachel Cargle opens her Brooklyn apartment door, I see the signs of relaxed living. There is the time to greet me slowly on a Monday morning. There’s the letter board displaying not an overcrowded schedule or a grocery list but the affirming words “This Too Is the Living.” There is the sunshine streaming in from a balcony where salad greens hang from a pocket plant wall. And there’s the soft, brandy-colored leather couch where we sit and talk over steaming cups of dark-roast coffee, served Jamaican style with thick condensed milk. Jamaica ranks among her happiest places.

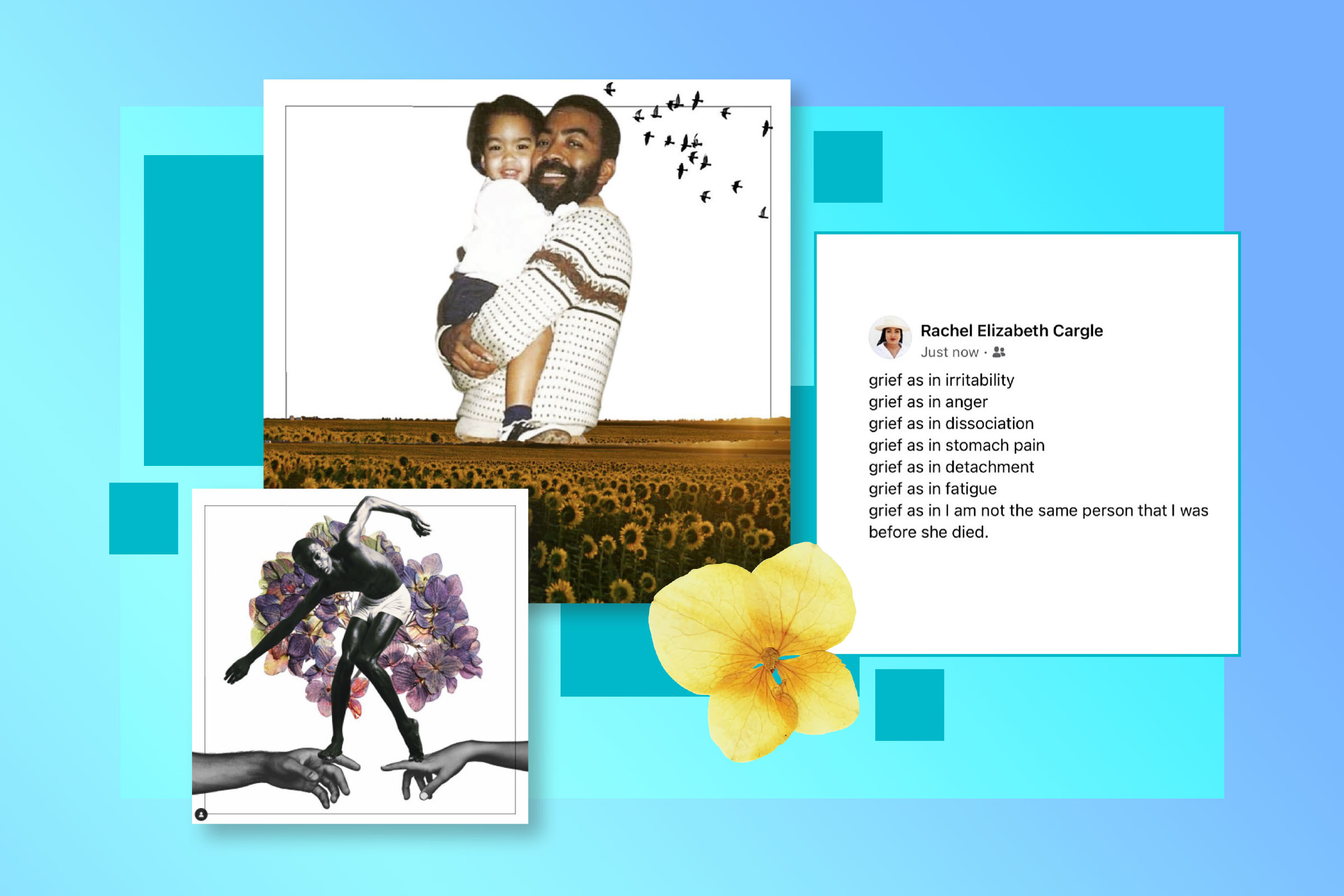

Cargle, 34, is a Black woman leading a modern, multihyphenate life, improbably filled with “an abundance of ease”—another of her favorite phrases. Her career as an influencer, speaker, and writer began about six years ago with the Instagram account @rachel.cargle; her posts on grief, self-care, liberation, and the conduct of “nice” white feminists have earned her 1.6 million followers. And she has over 1 million more following side accounts like @richauntiesupreme, which celebrates the life choices of women without children, and those for her businesses: a bookstore and writing center in Akron, Ohio; an online self-paced learning platform; and a foundation bringing mental-health support to Black women and girls.

Cargle, CEO of the Loveland Group (her collection of for-profit businesses), built her brand on her commitment to racial justice. But what makes her approach—and her life—particularly remarkable is her insistence that joy and pleasure are as essential as equity and justice in the making of a better world. “Racism causes our bodies to be weathered,” she says. “The repair of that requires being able to sit squarely in your values: you can find more peace when you are spending your time and energy doing the things you want to do, no matter how extraneous they may seem to anyone else.”

More from TIME

Read More: I Won’t Let Racism Rob My Black Child of Joy

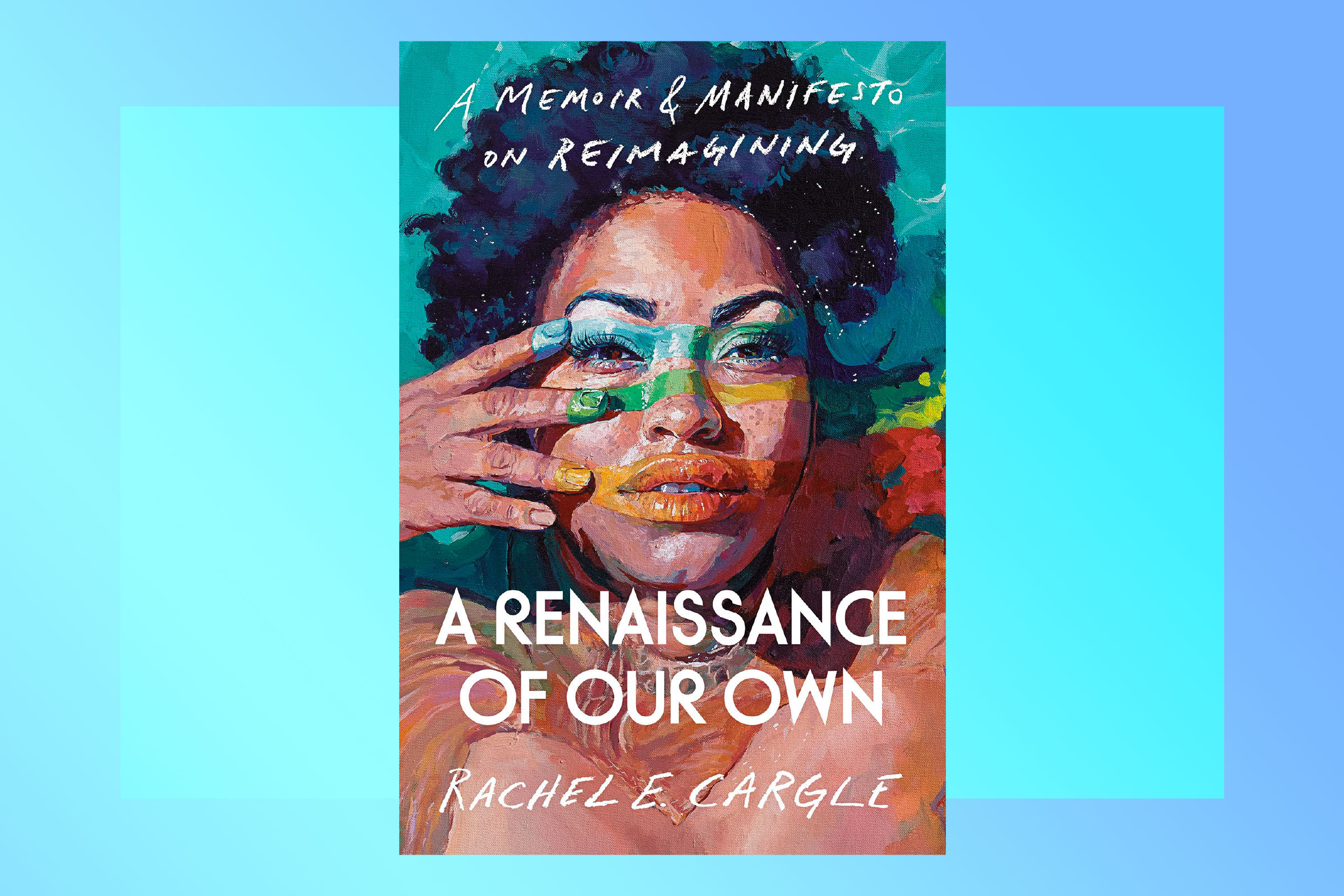

Her debut book, A Renaissance of Our Own: A Memoir & Manifesto on Reimagining, out May 16, is a collection of lessons and questions to prompt the reader’s own life redesign. The book and the worldview it illuminates are open to all, Cargle tells me, but it was written first and foremost for Black women. Because silencing, shaming, correcting, ignoring, downplaying, degrading, overburdening, and still demanding more from Black women remains the norm.

Cargle grew up the youngest in an Ohio family. Her father, a man who never provided steady financial support but showered Cargle with love, died of kidney failure when she was 11. Her mother, whom Cargle describes as industrious and creative, had been disabled by polio as a child. She was fixed on two things: religious salvation and survival. It was she who moved the family to subsidized housing in a nearly all-white, affluent area, hoping to provide Cargle and her two sisters with different opportunities.

As a teen, Cargle took note of the stoicism her mother cultivated. In the new book, she describes it as a response to difficult circumstances, the impracticality of falling apart. “We’re often in deep survival mode, Black women,” she says. “Softness was never offered as a tool.”

Cargle was a star student and, with her mother, a co-parent to her nieces, nephews, and one cousin. (An aunt spent time in jail, and she writes that her sisters became “victims of addiction” whose lives “collapsed in dysfunction and pain.”) Cargle was so convinced that caretaking, crisis, and welfare dependency were her future, she did not initially plan for college. At school she plastered on a smile. At home she contemplated jobs that would accommodate parenting but not render her ineligible for affordable housing. She shudders to admit how little she understood then about how race and income can shape one’s options. “Looking back on it now, I see that I was reaching for whatever good fruit I could find to pick off the blighted little tree I felt I had been assigned in life,” she writes.

With a cousin’s help, Cargle applied to the University of Toledo. But in 2009, before earning a degree, Cargle left school and followed the fellow student she’d married to his Ohio hometown, then into a U.S. Air Force guard unit. Outside her monthly service obligation, she worked at her mother-in-law’s daycare, then became a stay-at-home wife who hosted Bible studies. She tried to convince herself the security that a religious, military Black man and his orderly family presented would be enough. It wasn’t. After couples counseling with a Christian emphasis, she asked for a divorce in 2012. She also untethered herself from the idea that church was the only path to goodness.

These decisions began by simply imagining what else might be possible. “Sometimes I sit on a step and I rest there a while,” she says. “Sometimes I skip a few steps and sometimes I go back. You can’t do that when you are on this escalator of expectations from society, religion, family.”

By the time Donald Trump was inaugurated in 2017, Cargle had spent a few years living in Washington, D.C., and New York. She was dating, exploring her sexuality, and embracing polyamory. She was thinking and reading about gender and feminism. She was savoring the chance to watch Scandal while eating a burrito on the couch, alone. She’d bought into the ideal of the girl boss—women who seemed always in possession of “copious” glitter, Cargle writes in A Renaissance, and to conflate business success (or aspiring to it) with gains for all women.

As thousands converged on Washington and other cities for the Women’s March, a photo emerged of Cargle and her friend Dana Suchow, who is white, each raising a fist in protest. People online compared the picture to the iconic 1971 image of white feminist Gloria Steinem and Black childcare activist Dorothy Pitman Hughes, who together spoke about the importance of support for both the women’s and Black liberation movements. When the 2017 image reached @Afropunk, an Instagram account with mostly Black followers, the response was quite different. How, many commenters wondered, could Cargle find communion in that crowd of overwhelmingly white women, when nearly half of white women—47%—had voted for Trump?

Read More: Why Are Black Women and Girls Still an Afterthought in Our Outrage Over Police Violence?

Her answer: she still isn’t sure. She hadn’t learned much in school about Ida B. Wells, Mary Church Terrell, Anna Julia Cooper, or other Black women activists—people also hardly mentioned in the feminist texts she’d read as an adult. Only now was she learning white feminism had a track record of sidelining everyone else. So she educated herself, taking her evolving thoughts to social media. Her honesty about her need to learn and her obligation to bring accountability to her feminist work boosted her profile. Her following grew exponentially, also becoming far more diverse. What she was writing on social media led to speaking engagements where she was frank about the work that white feminism needs to do on itself and how her loyalties lie with those who have been most excluded and oppressed. That mission lead her, eventually, to create the Loveland Foundation.

The foundation began with an idea Cargle had in 2018 while briefly continuing college at Columbia University. There, she had access to affordable individual therapy for the first time. It helped her heal, and she wanted to improve access for others. To celebrate her birthday in 2018, she launched a GoFundMe and within months raised over $250,000.

Now an official nonprofit, the Loveland Foundation offers training to therapists of color as well as free mental-health care—it provided 6,202 Black women and girls with 74,424 hours of free therapy last year. Cargle hopes in the future to offer financial support to therapists and to create policy changes to boost diversity in the field. One major roadblock: the large number of unpaid training hours required to become licensed, which vary from state to state. In 2021, just 19% of the nation’s psychology workforce were people of color and 5% of these were Black, per the American Psychological Association.

Read More: How I Practice Self-Care as a Black Woman

The Sunday before I visited Cargle’s home, she and Sharlene Kemler, an experienced philanthropy executive who serves as CEO of the Loveland Foundation, hosted a brunch at a downtown Manhattan restaurant. There, they shared their own experiences with healing with a table of about 20 influencer guests. Kemler’s story—her family staged an intervention because she started therapy after her father’s death—set off knowing laughter and similar testimonials. Despite the diversity of their backgrounds and experiences as Black and Afro-Latino women, many around the table expressed that family distrust for mental-health care was a common challenge.

Cargle has a way of bringing whimsy to the most serious of purposes. On this rainy Sunday, she spoke of revolution while dressed in a sequined caftan. She strives to stay her easeful self at all times, especially as an employer whose behavior can impact others. “I don’t want to feel continuously at the mercy of the weather,” she says. She’s speaking metaphorically: the weather of politics, of people’s perceptions. “I want to be good whatever the weather is, and that takes a self-knowing,” she says. “That can’t be handed to you from anywhere—not from your parents, not from your religion, not from your job. Joy lives inside you.”

—With reporting by Mariah Espada

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at [email protected]