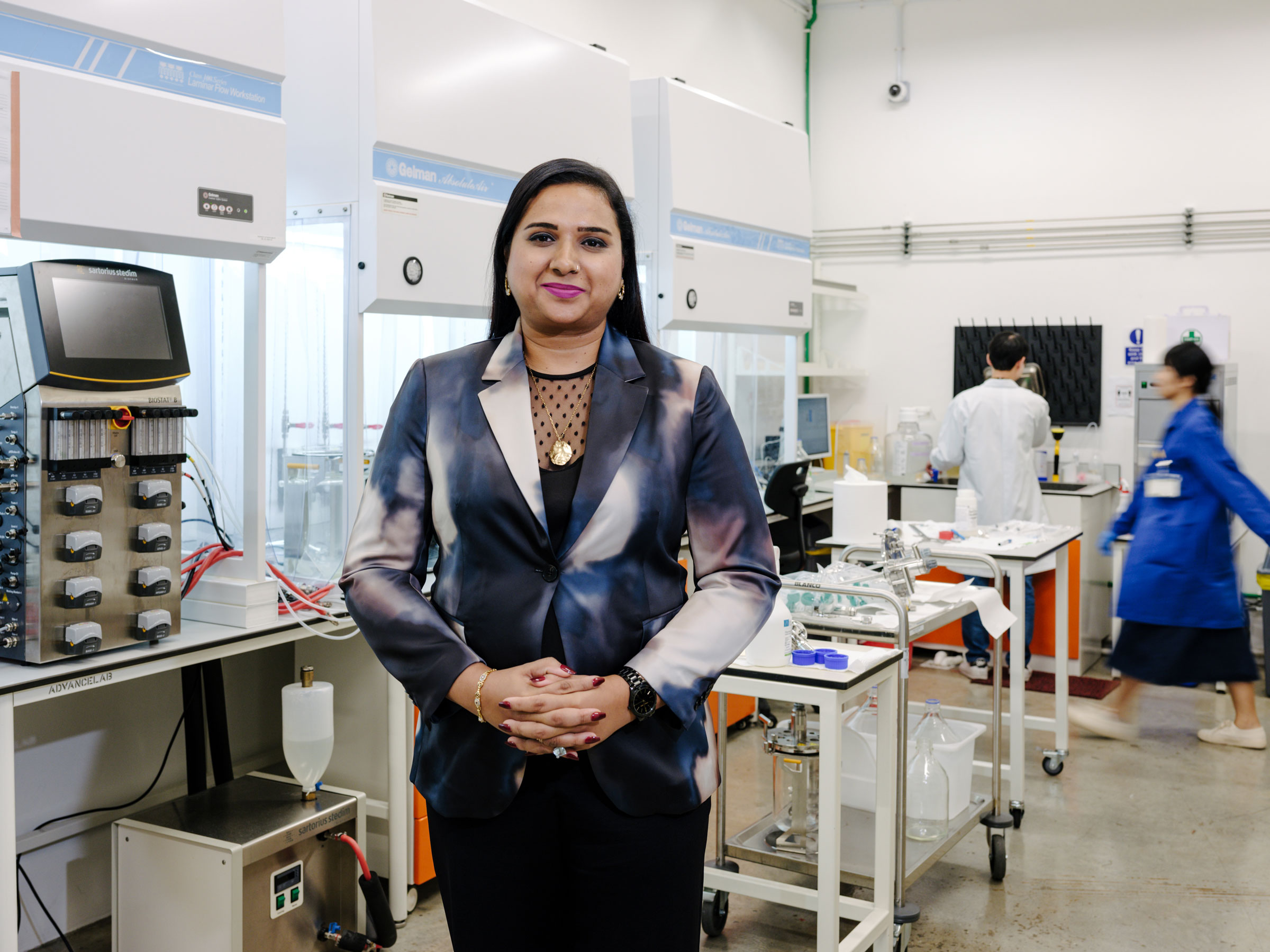

Sandhya Sriram is impatient. The stem-cell scientist wanted to put her knowledge to use developing cultivated seafood, but no one was doing that in Singapore. So four years ago, she set up a company to create lab-grown crustacean meat. Eagerly, she registered her company, Shiok Meats, at 3 a.m. in August 2018. “Nobody was doing crustaceans,” says Sriram, Shiok’s Group CEO and co-founder. “What do Asians eat the most? Seafood. It was a simple answer … And they’re so delicious.” A lifelong vegetarian, she had never tried real shrimp, but she sampled it the week she registered the company. Today, the results of her enthusiasm can be seen at Shiok Meats’ headquarters, in an industrial Singapore neighborhood. During a fall 2022 visit, a bespectacled bioprocess engineer clad in personal protective gear peered into a microscope. He had taken samples from a bioreactor in the room next door, where the company is culturing crustacean cells. Under the lens, he was checking to see if the cells were ready to harvest.

Shiok Meats has already unveiled shrimp, lobster, and crab prototypes to a select group of tasters, and it plans to seek regulatory approval to sell its lab-grown shrimp by April 2023. That could make it the first in the world to bring cultivated shrimp to diners, putting it at the forefront of the cultivated-meat race. As of this writing, only one company has gained regulatory approval to sell lab-grown animal-protein products: Eat Just’s cultured chicken is available—but only in Singapore. Shiok Meats still needs to submit all the paperwork necessary and get regulatory approval, but the company hopes to see its products in restaurants by mid-2024, offering foodies a cruelty-free and more environmentally friendly option than crustaceans from farms.

But even if that ambitious timeline is met, it will likely be a while before the average person is eating cultivated crustaceans. It will require not just regulatory approval but also more funding and a bigger factory, along with persuading consumers and governments around the world to accept lab-grown seafood. “We’re at an interesting stage of a startup; it’s called the Valley of Death,” says Sriram. “We are in the space where we haven’t submitted for regulatory approval yet, but we’re looking to commercialize in the next two years.” Nevertheless, the impatient entrepreneur is optimistic. Sriram hopes to have the company’s next manufacturing plant ready by the end of 2023, where a 500-liter and a 2,000-liter bioreactor will be a major scale up from its current 50- and 200-liter bioreactors. The goal is for her products to enter the mainstream in Singapore in five to seven years.

Popularizing these products could help tackle some of the environmental impacts of crustacean production. Organic waste, chemicals, and antibiotics from seafood farms can pollute groundwater and coastal estuaries. Hatcheries are often in places that may otherwise be home to mangroves that can sequester carbon and protect vulnerable coastlines from storms, says Sriram. A 2018 Nature study found that production of crustaceans—measured by the weight of edible protein—can result in carbon emissions comparable to beef and lamb. That’s in part because of how much fuel is used in fishing boats proportional to the end-product amount of protein obtained. And although shrimp and lobster accounted for only 6% of seafood (based on 2011 data), the study found they represented 22% of the industry’s carbon emissions. Shiok Meats says the way it produces crustacean meat minimizes animal cruelty, as growing protein in a lab helps avoid killing animals. Trawling vessels that ensnare bycatch are also avoided. And cultivating shrimp closer to where it’s consumed cuts emissions from fishing-boat fuel and shipping products around the world.

Asia consumes more seafood than any other region. Several food-tech companies are tapping into this demand, including a Hong Kong company making lab-grown fish maw, a Chinese delicacy, and a South Korean company also developing cultivated crustaceans. But Shiok may have a first-mover advantage. In 2018, it filed for a patent covering how to use stem cells from crustaceans to make food—which it’s hoping to receive in the next year or so; it could then license its technology to other companies. Diversifying how and where the world gets its seafood will be crucial for feeding Asia’s fast-growing population, which is expected to increase by 250 million by 2030. Singapore’s authorities, at least, are keenly aware of the challenge. The Southeast Asian city-state—which lacks farmland and imports 90% of its food—is aiming to produce enough food to meet 30% of its nutritional needs by 2030 (up from less than 10% in 2021). Hoping to become Asia’s food-tech capital, Singapore is focusing on innovations like plant- and cell-based proteins; these “require far less space and resources to produce the same amount of food as traditional food sources,” Bernice Tay, director of food manufacturing at Enterprise Singapore, a government agency that supports small businesses, told Nikkei Asia. In December 2020, Singapore became the first country to approve the sale of cultivated meat—the chicken product from Eat Just—to the public.

Sriram says the government has helped Shiok with grants, in matching venture-capital funding, and in hiring foreign talent. The company has raised about $30 million, with backers like the Netherlands-based aquaculture investment fund Aqua-Spark, South Korean food giant CJ Cheil-Jedang, and Vietnamese seafood company Vinh Hoan. Fundraising is challenging, says Sriram, and it’s expensive to scale up manufacturing—which is being hampered by a global shortage of stainless steel, needed for the bioreactors.

Ultimately, the company’s goal of feeding the world will be contingent on other governments getting on board with lab-grown meat. Then there’s the need to persuade consumers to eat the stuff. Price is also a barrier. Shiok shrimp’s launch price will be about $50 for 2 lb., nearly two to four times the price for fresh or frozen prawns at the grocery store. Sriram envisions launching Shiok’s crustacean meat as a premium product at first, where some restaurants could offer it in select dishes to diners willing to pay the price. She also plans to work with food manufacturers like CJ CheilJedang to create ready-to-eat products like dumplings. “The vision,” she says, “is to have sustainable, delicious, healthy food for everybody, without animal cruelty.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Amy Gunia/Singapore at [email protected]