Khadidah Stone, 26, has lived in Montgomery, Alabama for most of her life. Under Alabama’s newly drawn congressional map based on the 2020 census, she votes in Congressional District 2. But last November, Stone was among the Black Alabamians who sued and challenged that map, arguing it illegally dilutes Black voting power.

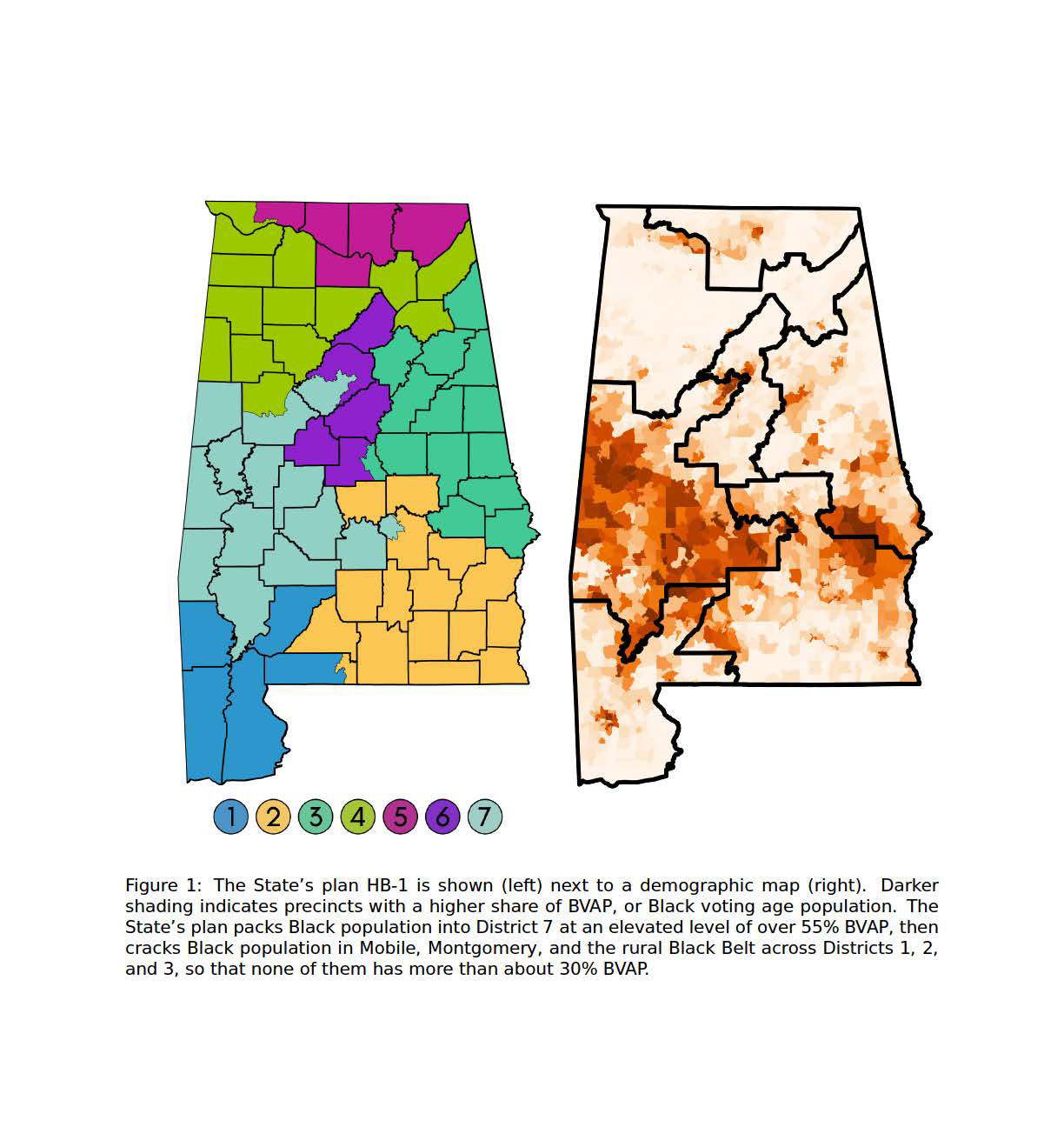

Stone, her co-plaintiffs, and the advocacy groups the Alabama State Conference of the NAACP and Greater Birmingham Ministries allege that the state’s redistricting violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits state governments from limiting voting on the basis of race, including through “vote dilution” by either intentionally carving up communities of color up among districts or squeezing them all into one. The plaintiffs argue that the new map illegally “packs” most of the state’s Black voters into the 7th Congressional District and “cracks” the remaining Black voters in Mobile, Montgomery, and the rural Black Belt into Congressional Districts 1, 2, and 3.

In January, a federal court agreed with them. A panel of three judges—two of whom were appointed by former President Donald Trump—struck down Alabama’s map and directed the state legislature to produce a map that either included another majority-Black district or “an additional district in which Black voters otherwise have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice.” Alabama appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which voted in February to reinstate the map until litigation plays out. When Alabama voters head to the polls in November, they will be voting in districts a federal court deemed are likely illegal.

On Oct. 4, the Supreme Court is poised to hear the case, Merrill v. Milligan. The stakes extend beyond Alabama’s electoral map. The court’s ultimate judgment could further damage the Voting Rights Act, undermining the most powerful tool for prohibiting racial discrimination in voting.

Alabama argues that the lower court’s order for lawmakers to draw a second majority-Black district would amount to creating “racially segregated” districts that violate the Constitution. “Section 2, as constitutionally conceived, is a shield against racial discrimination,” Alabama argued in court filings. “It is not a sword to perpetuate it.”

The plaintiffs argue that race has long been one of many factors map-drawers might use to delineate communities of interest for the purpose of redistricting. They also point out that race is often highly correlated with political leaning in Alabama. Stripping Section 2 of the consideration of race, they say, could neuter the provision’s ability to fight vote dilution all together.

“It essentially would turn the entire Voting Rights Act on its head,” argues Yurij Rudensky, senior counsel in the Brennan Center for Justice’s Democracy Program, which filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs. “It’s hard to imagine how racial discrimination can be remedied without some consideration of race.”

Read More: Voting Rights Isn’t Just a Black Issue.

More from TIME

Section 2 has served as the Voting Rights Act’s primary enforcement tool ever since the Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder gutted other portions in 2013. In July 2021, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee that two controversial voting laws did not violate Section 2, weakening the federal regulation even further.

Voting rights advocates now argue that if Alabama prevails, it could diminish the law’s remaining power. For Stone, the possibility that the Voting Rights Act could be crippled in Alabama—a state whose struggle for civil rights gave rise to the legislation—is frightening.

“It would be a harsh reality if the results were not turned in our favor,” she says. “Power is on the line.”

Both the Alabama Attorney General’s office and the Alabama Secretary of State’s office declined to comment on pending litigation.

How to prove vote dilution

To win a vote dilution claim under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, plaintiffs must first pass what’s known as the “Gingles test.” Based on the 1986 Supreme Court decision Thornburg v. Gingles, the test requires plaintiffs to draw examples of other maps that wouldn’t dilute minority votes to prove that it’s possible under existing redistricting principles. Plaintiffs then need to prove that the minority group in question is politically cohesive and typically votes for different candidates than the district’s (usually white) majority.

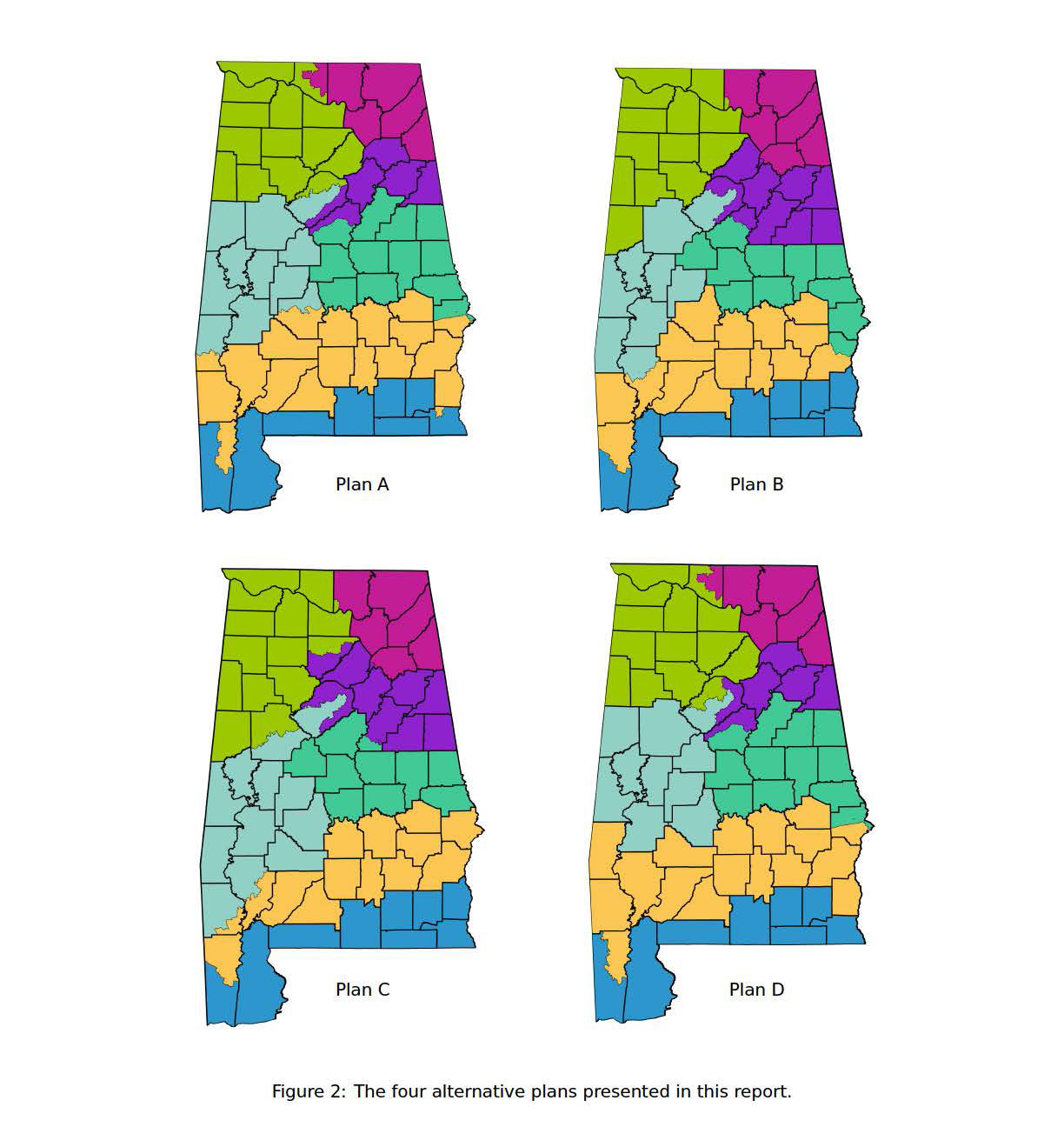

In Alabama, the plaintiffs first had to provide the district court with maps that proved it could be possible to draw either a second majority-Black district or an additional district where Black voters could elect representatives of their choice. They submitted 11 alternate maps. Under at least four of those maps, Stone would no longer vote in District 2; instead, she would live in a new majority-Black district. Alabama argued the maps “diverge significantly” from prior designs that respected the “unique industry and culture of the region.” Lawyers for the state also noted Alabama’s congressional districts have looked much the same for decades, and since 1992 have only had one majority-Black district.

The state also made an even more ambitious argument: The only way the plaintiffs could have drawn a second majority-Black district was to “intentionally sort Alabamians by skin color.” Doing so, they said, would violate the Constitution.

The plaintiffs responded that the state’s argument contradicts the Supreme Court’s ruling in 2009’s Bartlett v. Strickland, which held that a minority group must make up more than 50% of an area’s voting population in order for Section 2 to mandate the creation of a majority-minority district. How can states draw majority-minority districts, the plaintiffs responded, if they can’t consider race?

The district court agreed with the plaintiffs. Banning the consideration of race when drawing alternate maps would prevent “any plaintiff from ever stating a Section Two claim,” the panel ruled in January, adding that if “Section Two is to have any meaning, it cannot require a showing that is necessarily unconstitutional.” The three-judge panel not only found that “Black Alabamians are sufficiently numerous to constitute a voting-age majority in a second congressional district,” but also concluded that “Black voters have less opportunity than other Alabamians to elect candidates of their choice to Congress.”

Alabama appealed, arguing that the district court’s ruling illegally compelled the state to prioritize race above “race-neutral” redistricting criteria. They argued that the original plan “was consistent with stated redistricting priorities: make race-neutral adjustments for small shifts in population over the last decade, but otherwise retain existing district lines.”

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal, voting 5-4 to leave the map in place until they’ve issued their decision.

John Roberts and the Voting Rights Act

The key jurist to watch in the case is Chief Justice John Roberts, the lone member of the conservative majority who did not vote to reinstate Alabama’s map. In a dissent that argued against keeping the map in place while the high court considered the case, Roberts wrote that the district court had followed the law and applied the “Gingles test” correctly. But, he continued, the existing law has clearly caused confusion and showed that Gingles is worth revisiting and clarifying.

Voting-rights advocates worry about what kind of clarification Roberts may have in mind. Senior Counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund Deuel Ross argues if the high court agrees with Alabama that experts cannot consider race when coming up with proposed fixes for vote dilution, it would make it challenging to raise any Section 2 claims at all.

“That will make it really difficult for every state, every city, every county in the country to draw their maps going forward in a way that respects minority communities,” says Ross, who represents the plaintiffs. “And will potentially have a really devastating impact on representation for communities of color.”

Roberts’ career was marked by cases that weakened the Voting Rights Act before he joined the Supreme Court. He then wrote the majority opinion in 2013’s Shelby County, striking down the formula that determined which jurisdictions had to receive federal approval to change their voting laws. “Our country has changed,” Roberts wrote in his majority opinion, arguing that the preclearance formula that calculated those jurisdictions was now unnecessary because it was based on decades-old data. In her famed dissent, then-Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote that the decision was like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Read More: Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Dissent in Shelby County Was a Warning.

What remains of the Voting Rights Act could now once again fall to Roberts. Like other high profile cases that will appear before the court this term, the bench’s 6-3 conservative super majority is being asked to determine to what extent race and ethnicity should be considered in American law and society. And what they decide could be a final nail in the coffin of the most powerful federal legal protection for ensuring equitable access to the ballot. Federal protection that Rudensky argues is “no less important to ensuring that we have a healthy democracy now as it was when it was first enacted nearly 60 years ago.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at [email protected]