Chuu Wai Nyein felt an overwhelming sense of guilt when she first arrived in Paris from Myanmar at the end of April. “I was pushed to leave the country, but it was not how I wanted to leave,” says the 28-year old. As an artist working for the last ten years, mostly in the central city of Mandalay, Chuu built up an international reputation for her expressive paintings of women. Now, forced to leave because of intimidation from authorities, she has been trying to start over in France, adapting from the intensity and violence of her home country to the relative peace of her new location. “During my first week here, I felt guilty when I walked outside on the street, because I’m still alive,” she says. “I felt like it’s not fair for the other people I left behind. Even when I smiled or felt happy, I also felt guilty.”

Myanmar’s military overthrew the country’s leader Aung Sang Suu Kyi in a coup on Feb. 1. At first, a surge of creativity in protest art, posters and poems flooded both the country’s streets and social media platforms. But in the five months since, an escalation in violence from the military, and a growing armed resistance movement, has put the country on a dangerous path towards all out civil war.

On June 17, the U.N.’s office in Myanmar released a statement saying it was “alarmed at recent acts of violence that illustrate a sharp deterioration of the human rights environment across Myanmar.” It pointed to the discovery of two mass graves of people “who had reportedly been detained” by the Karen National Defense Organization, a rebel militia, and to the burning of more than 150 homes, reportedly by government troops, in the central Magway region in June. According to local monitoring group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, the junta has killed more than 870 people, and more than 5,000 were under detention as of June 20.

Read more: The World Has Failed Myanmar. So Now Its Youth Are Stepping Up

The heightened danger and violence under the brutal crackdown has forced journalists, artists, filmmakers and writers into hiding, staying one step ahead of the security forces, with an increasing number fleeing to border areas or into neighboring countries, says Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch. Some, like Chuu, have been able to flee even further afield, hoping to do what they can from afar to help those back home.

Chuu had plans to move to Yangon and set up her own studio, and was looking for locations in the city, when the coup happened. She started off feeling helpless, not knowing what to do as Internet and communications blackouts ensued in the immediate aftermath of Feb. 1. “I thought, maybe what I can do is paint, and I can collect people’s opinions and feelings in their own handwriting,” she says. She collaborated with other local artists and art students to start a demonstration called Write for Right, encouraging demonstrators at the daily street protests to write down what they hoped for and wanted. Many of them wrote “democracy” during those early days.

Chuu continued her work at the protests through February and March, joining with women’s rights groups to bring art to their protests, and donating the proceeds of the sale of some of her paintings to the country’s Civil Disobedience Movement. But as the violence escalated, and several other artists were detained in late March, Chuu and her collaborators on the Write for Right project hid their evidence and went underground with their activities. Just a few days after Chuu smuggled several Write for Right posters out of her apartment, trucks of police and soldiers searched her building several times and she was questioned by police. It was that moment, combined with calls from former colleagues encouraging her to leave if she could, that changed her mind. “The feelings change when groups of people are standing in front of your door, and suddenly you realize you are fighting something so unfair, and they can do whatever they want: they can break the door, they can touch you, or they can just shoot you right on your doorstep.”

“Since the coup, I’ve dreaded waking up every day,” says another artist known by the moniker Bart Was Not Here, who was interviewed by TIME in February using a pseudonym for his safety. Bart too left Yangon for Paris, arriving in early June to take up a six-month-long artist residency with Cité Internationale des Arts Paris. He wanted to leave Myanmar last year to live in the U.S., but the COVID-19 pandemic followed by the coup upended his plans. For Bart, 25, the decision to leave wasn’t so much about feeling personally endangered, as it was about the inability, in such a volatile situation, to create the art he wanted to make. “I make art, I think so highly of art, and art history is beautiful. All of these things go out the window once people start shooting each other. You can’t win a war with art. It breaks me and makes me sad, and I had to accept it.”

“When a lot of young creatives like me leave the country, it’s going to be a huge setback for a long time,” says Bart, adding that it’s not only artists affected, but young entrepreneurs and young professionals in other fields, some of whom studied abroad and came back to Myanmar after elections in 2015 to help build their country’s future.

Both Bart and Chuu want to dedicate their time in France to raising funds for those on the ground back home. This month, Bart’s work has featured in a fundraising project by U.K.-based social enterprise Migrate Art, and the sale of artwork and posters for the project has so far raised £25,500 ($35,547) for Mutual Aid Myanmar. Chuu is also looking to do all she can to help and find connections with galleries in France willing to support her and her work.

Read more: How Myanmar’s Protests Are Giving a Voice to LGBTQ+ People

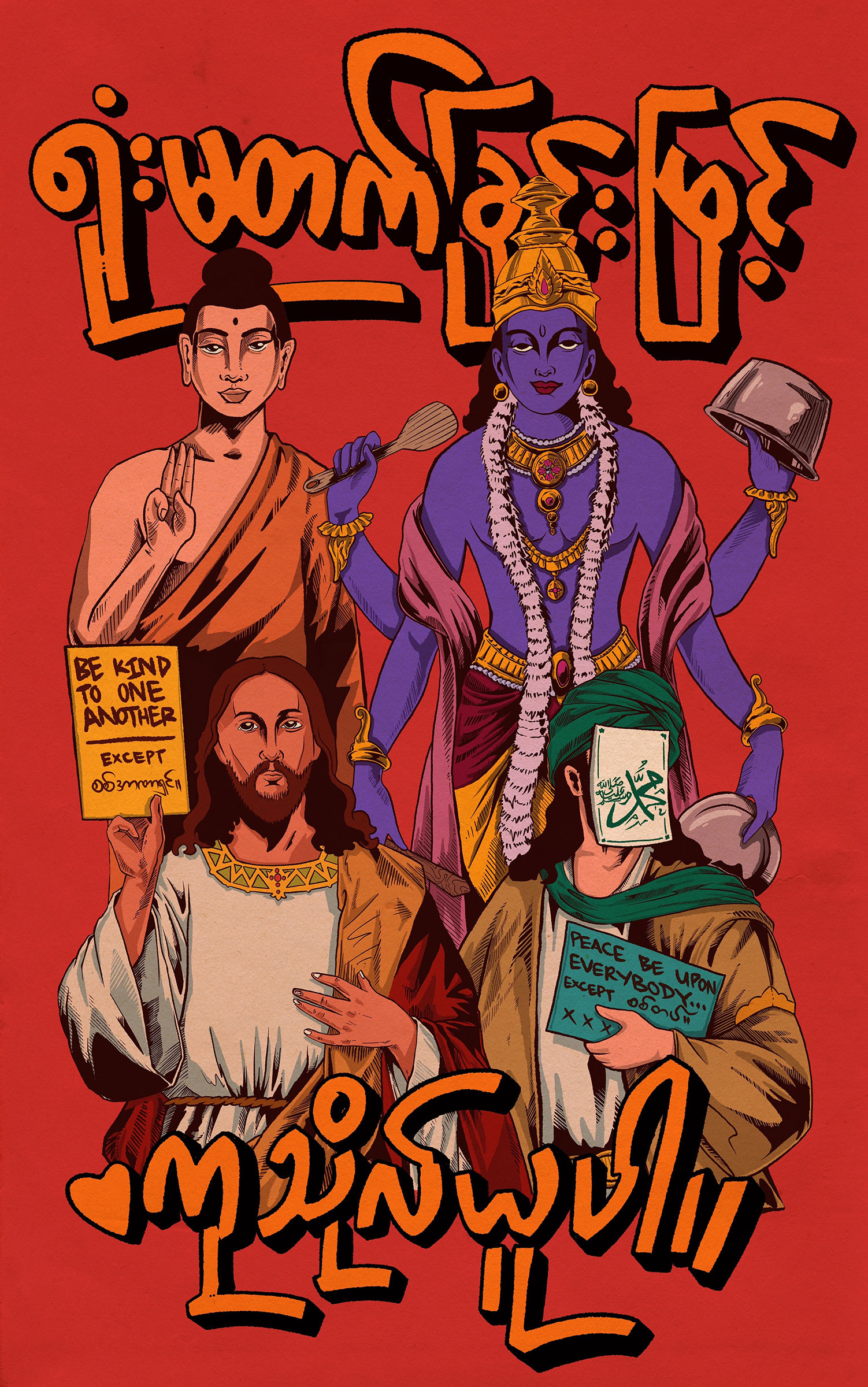

“The military junta is moving full throttle to try to stamp out freedom of expression, art and film, and the independent media that grew up over the past decade under the previous civilian governments,” Robertson of Human Rights Watch tells TIME via email. “But this time around, the military severely underestimated the people’s determination to resist, especially among the youth who are not willing to give up their freedoms to express themselves, and are now employing innovative ideas and tactics to continue the protests with various unifying themes.”

Robertson points to the June 19 ‘flowers in the hair’ protests on social media, marking the birthday of ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who is currently on trial for a wide range of criminal charges, as an example of protests rallying solidarity online. “These creative people are continuing to spark support and unity among the Burmese people, and will continue the fight even from the shadows where the junta has forced them to hide,” he says.

For Bart and Chuu, who have both posted their photographs from their new locations to social media, that fight is continuing far beyond Myanmar’s borders. “Not a lot of people have a chance to leave the country,” says Chuu. “I’ve realized there is a reason for me to help and to work. Even if it’s small and not efficient, I will keep demonstrating wherever I will be. I will keep going.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at [email protected]