The supreme thrill of sharing space with others has never been so keenly felt—or missed—as in the past year. In a time marked by immeasurable loss, fear and upheaval, pods and social distancing entered the common lexicon, their frequent use serving as constant reminders of both our hunger for connection and its current limitations. So too did BIPOC, the acronym for Black, Indigenous and people of color—and it was these communities who not only highlighted the inequities of a system that wasn’t built for them but also created spaces that helped provide joy, comfort and sustenance during a year unlike any other.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that the shared values of care and compassion have largely defined the fellowship of marginalized communities during this time, given the long history of stepping up for one another when society has failed to do so. If mutual aid and community fridges were embraced by the mainstream last summer, BIPOC-led organizations throughout history—like the Black Panther Party with its free-breakfast program and health clinics—have always served as vital support systems.

Here, we highlight five of these community pods that follow in this legacy of care. While many were formed or solidified in the wake of converging cultural shifts from the pandemic and a national reckoning over race, they are also defined by shared interests and purposes. From NorthStar, a Seattle cycling group that has grown by nearly 97% since it began last year, to a Buffalo, N.Y., photography studio pod that offers professional and personal support to its members, these groups have provided much-needed respite and solidarity.

Their members have long been disproportionately affected by health, economic and racial inequalities, which have only been exacerbated this past year. In some cases, experience with such hardships made them better equipped to face them. House of Grace, a support network for queer and trans folks in Puerto Rico, began work in this space before the pandemic, and reaffirmed its mission in the face of a new crisis.

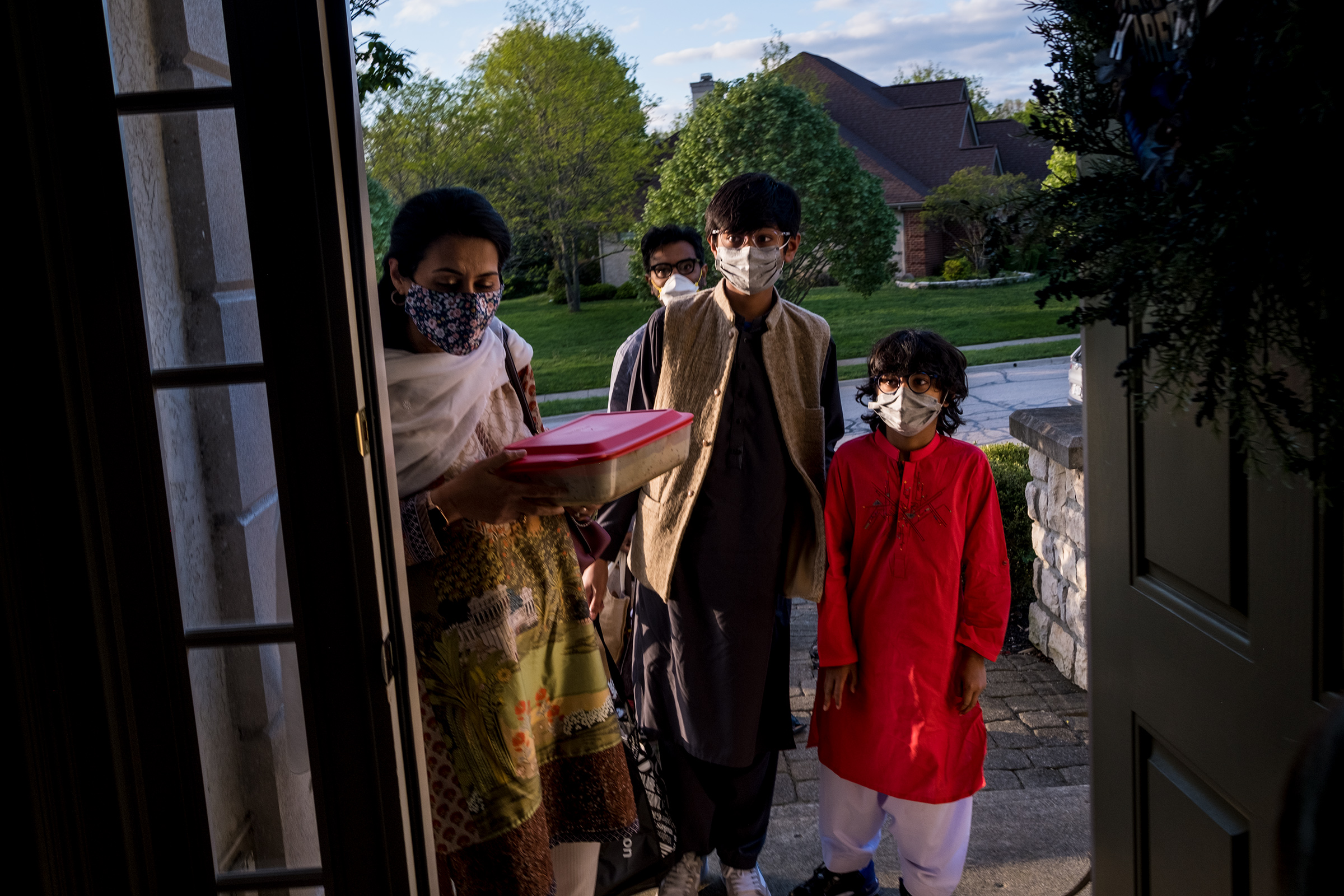

The pandemic has also redefined how we come together; meeting doesn’t have to take up physical space, but it can still be emotional, spiritual and fulfilling. When Ramadan began soon after the pandemic took hold in the U.S. last spring, Imran and Atifa Malik’s family missed the celebrations that once defined the holiday. That inspired them to bring together members of the larger Muslim Ohio community virtually—which eventually became an in-person space for connection across families and generations.

Meanwhile an online course about identity and history sparked a connection between a group of Asian-American women across the country. It soon led to a group chat and monthly Zoom hangs. “I feel so bonded to them, even though their experiences might not be exactly the same as mine,” Amy Ding says of her new virtual cohort. “As Asian women, there was deep healing and a deep yearning for more of this type of community.” At a time in which staying 6 ft. apart has often hampered intimacy, communities of color have provided a different path forward and created connections that promises to outlast a period marked by uncertainty.

—Cady Lang

Seattle

NorthStar Cycling Club takes its name not just from the sky, but also from history—the star Harriet Tubman used as a guide to free enslaved Americans. “When we get on our bikes, it is an element of freedom,” says founding member Edwin Lindo, who launched the cycling club based in Seattle in February 2020, just before the pandemic started. He and co-founder Aaron Bossett wanted to encourage more BIPOC individuals to take up cycling. Lindo, who identifies as Central American, attributes the lack of diversity in cycling to attitudes that often focus on questions like: “Do you have the nicest bike?” or “Do you have the fastest bike?” This culture, he says, is not welcoming to individuals who might not have the means to take up the sport. “There’s an archetype of cycling— we’re not it.”

The community has grown to more than 140 members who connect virtually on Slack, with anywhere from 25 and 85 participating in Sunday rides for people of all levels and ages. The group is about blending political issues like police brutality and racialized health inequities with riding, in a spirit of inclusivity that extends to the cycling novice: In early May, one participant learned how to brake on a bike, then rode 18 miles with the group. “It has been a point of grace and inspiration and absolute joy and freedom,” Lindo says. “I don’t know what I would do without it.”

—Kat Moon

Buffalo, N.Y.

The photographers came together at a time when the pandemic had largely shut down film and TV production, magazine shoots and other fields that generate photography-related assignments. Based in Buffalo, N.Y., Adrian Javon, Malik Rainey, Derrick Carr and Brandon Watson—four Black men in their 20s specializing in areas ranging from advertising and commercial photography to photojournalism—formed a studio pod to support each other in continuing their work. “We were all we had,” says Rainey, 21. They’re able to share opportunities whenever one hears of something that might be a fit for another. “In our group, what we believe is uplifting each other. It’s no such thing as competition with us.”

In their work, they seek out Black and BIPOC talent. In what Rainey describes as a “very whitewashed profession,” they are eager to show it’s possible to be a successful Black photographer. And the photographers’ bonds with each other have strengthened since the pandemic began. While in the studio, they talk about everything from relationships to comic books. “It’s not always photography-related,” Rainey says. “Because at the end of the day, we’re human beings first; we’re artists second.”

—Kat Moon

Puerto Rico

In 2018, trans activist and poet María José started House of Grace to create a community where trans and nonbinary people of color in Puerto Rico could safely explore their identities. The need for spaces like these has only become more urgent: the Human Rights Campaign reports that at least 12 LGBTQ people have been killed in Puerto Rico since the start of 2019, and the island’s governor declared a state of emergency over gender violence on Jan. 24. “This is such a cruel world to us,” says Coqueta, a 25-year-old trans dancer, one of 12 members in the House of Grace collective, who meet and live in locations including Guaynabo, Río Piedras and Toa Baja. “All the members of the house have chosen this as their family because they know they don’t have the same support elsewhere,” she says. Beibijavi, 23, had left their biological family’s house—“It wasn’t a safe space for me,” they say—and lived intermittently with different members of House of Grace during the pandemic. Among the collective, self-care, collaboration and mutual support are key. “That’s our foundation: we got each other,” Coqueta says.

—Kat Moon with reporting by Alejandra Rosa

VirtualThe women first met in an online course in October 2020. Hosted by AARISE (Asian American Racialized Identity & Social Empowerment), the six-week-long class centered on Asian American history and identity with a component on emotional processing and healing. “It personally spoke to me because it was supposed to be a program and community that was focused on social justice and liberation,” Amy Ding, 24, says of why she decided to take the course. Following the murder of George Floyd, Ding felt compelled to learn more about her Asian American identity to be a better BIPOC ally. Ding and the six other Asian American women—ranging in age from their mid-20s to late 30s—wanted to continue to meet regularly after the course ended. Located across the U.S. in states from New York (where Ding lives) to Missouri to Texas, they started a WhatsApp group chat and have met virtually on Zoom every month since January.

In these video calls, the group discusses topics ranging from books and podcasts that celebrate Asian American voices to navigating relationships, both personal and professional, as Asian American women. At times the conversations are lighthearted, and at others the women share their stories about microaggressions and racism. “There’s definitely been a lot of experiences of being gaslit,” Ding tells TIME of her identity as an Asian woman in America. “When I think of how I’ve been supported by this group, a lot of it is feeling reaffirmed that there are other people who know what I’m talking about or who understand the hesitations of having [thoughts] like, ‘Oh, was that racist?’”

Following the Atlanta-area shootings on March 16, the community formed through AARISE was also a source of support for Ding. “I remember that moment being very tender for me, and this was certainly a group that I relied on,” she says. Although the women have not yet connected face-to-face, they share a tangible bond. “It’s feeling really seen and heard by these women,” Ding says of the group’s impact, “which is funny because I haven’t met any of them in person.”

—Kat Moon

Dublin, Ohio

For Imran and Atifa Malik’s family, Ramadan in 2020 was just not the same. “It’s the time to get together and celebrate and share in blessings and do community work,” Atifa, 44, says. “With the pandemic, we didn’t have that.” Her family, along with many others in and around their Columbus suburb, could not go to mosques or drop off food in each other’s homes as is customary. Instead, Atifa and some friends arranged for their kids to recite the Quran together online. “That way at least they still have that interaction,” she says. Her family and several others that were close before the pandemic formed a multigenerational group to regularly connect virtually.

This Ramadan, following the vaccinations of most members of these families, some of those interactions are shifting from virtual to in-person. The Maliks were joined by four other families on the evening of May 5 to break fast together with iftar, the evening meal eaten after sunset. “We’re trying to get some normalcy in our lives,” says Afsheen Rizvi, 45. Rizvi one of the mothers who attended the iftar, has three sons aged 8, 12 and 16. “Living in this country, being a minority, we depend on each other, our community, and especially the religious aspects,” she says.

Before the in-person events resumed, Atifa says the group’s online gatherings provided emotional support in some of her toughest moments from last year. “There were complications with my sister’s pregnancy. My mother’s health was declining, so to cope with that we ended up doing Zoom meetings and doing prayers together,” she shares. “It was a huge blessing.”

—Kat Moon

Correction, May 13

The original version of this story misstated Kari Lu Cowell’s name. It is Kari Lu Cowell, not Kari Lu.

Correction, July 22

The original version of this story misstated who photographed the group in Buffalo, N.Y. The photograph was created in collaboration between Derrick Carr, Adrian Javon, Malik Rainey, Joshua Thermidor and Brandon Watson for TIME. It was not photographed by Malik Rainey for TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Cady Lang at [email protected]