Sándor was around 7 when, in 1938, German soldiers came to his town in what was then Czechoslovakia.

One by one, Sándor’s friends and neighbors, who were members of the Roma ethnic group, were taken away by the Einsatzgruppen, who were Nazi security forces. They were supposedly taken to check their IDs, but they never came back. By the age of 10, Sándor had seen many of his remaining neighbors murdered.

But the boy had musical talent, and the soldiers liked to listen to him play. On stage, hands trembling as he held his violin, he would witness the horrors of the German Reich, seeing Roma women led past his stage to be raped by the Nazis. Sándor, who died in 2000, was able to survive Nazi persecution because of his music, but hundreds of thousands of Roma were murdered during the Holocaust. Many more faced persecution, displacement, forced labor, forced medical experimentation and sterilization, violence and imprisonment.

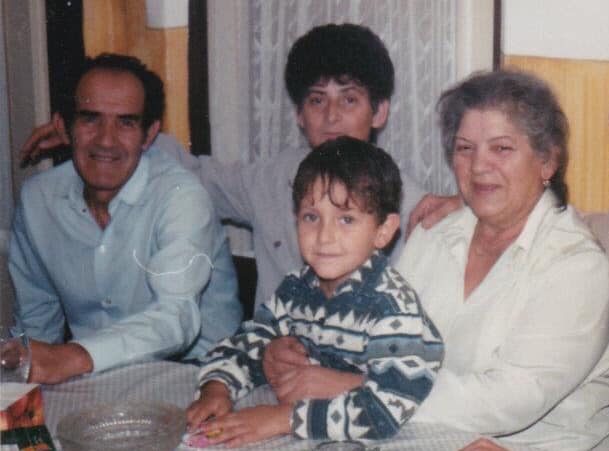

More than 80 years later, their descendants — including Sándor’s granddaughter Daniela Abraham — are fighting for recognition of that often overlooked part of history.

“I can’t imagine how horrific it would have been for my grandfather to have to continue to play music while seeing what was going on in front of him,” Abraham tells TIME. “The Roma genocide, where whole communities of Roma were destroyed by the Nazi regime, is often forgotten.”

Roma and Sinti people, often derogatorily referred to as “gypsies,” are members of an ethnic group with deep roots across Europe. While Sinti are of Western and Central Europe origin, Roma are those of Eastern and South Eastern Europe origin. The term Roma is often used to describe this community as a whole. Today, Roma communities are spread across Europe and the U.S., and many are still marginalized, but the Holocaust represents an ugly peak in that history of persecution.

Abraham set up the Sinti Roma Holocaust Memorial Trust in 2018 in the hope of bringing the Roma genocide into mainstream consciousness. “I don’t want our people who have suffered at the hands of the Nazis to be forgotten. They deserve to be remembered,” Abraham says.

The often overlooked persecution of Roma living across Europe is also now the focus of a new exhibition at The Wiener Holocaust Library in London, Forgotten Victims: The Nazi Genocide of the Roma and Sinti, on view for the next five months. The exhibition, curated by Barbara Warnock, features the stories of Roma subjected to Hitler’s terror. Their fates have been discovered using the International Tracing Service (ITS) digital archive, which was established to trace those lost and missing during World War II and the Holocaust.

“The exhibition is really important in exposing what happened,” Warnock tells TIME. “Even when people are aware that Roma were targeted by the Nazis — and often people aren’t — it’s rare that people actually know any details about it.”

Heightened persecution

While the discrimination against Roma began centuries before the Nazi era, their treatment worsened drastically following Hitler’s accession to power in January of 1933. By the mid-1930s, the Nazis had banned Roma from working in certain jobs, Roma were subjected to forced sterilization as a form of ethnic cleansing, and a large number were sent to special internment camps.

An estimated 500,000 Roma were killed, but the precise number is unknown — in part because many murders were unrecorded — and some researchers argue that the true death toll is higher. The number is small compared to the estimated six million Jews killed during the Holocaust and the Roma were not central to the Nazis’ hateful ideology, but they were similarly regarded as a threat to the “Aryan master race.” Warnock estimates that the death toll represented about a quarter of the Roma population.

“A majority of the Roma never even made it to the camps, they were simply murdered whenever they were found, and their deaths went unrecorded,” Abraham says. “This is why there is such a major discrepancy between ‘official’ death tolls based upon Nazi records and the actual losses to our population.”

Following the German army’s invasion of Austria in March 1938, the persecution of this group intensified. More than a thousand Roma and Sinti in Germany and Austria were sent to concentration camps where many were murdered.

During this time, everything changed for Hermine Horvarth, a 13-year-old Roma girl living in Jabing, Austria. Her father was taken to Dachau concentration camp in June 1938, leaving Horvarth with her pregnant mother and five siblings.

“I noticed quite soon that the local [SS leader] had no qualms about any racial problem when it was a matter of a young gypsy girl,” Horvarth told journalist Emmi Moravitz in February 1958. “He kept pestering me. One day he suddenly appeared in front of me with a pistol at the ready.” But Horvarth, whose testimony to Moravitz is featured in the Weiner Library exhibit, escaped and told the SS leader’s wife. His wife demanded that Horvarth repeated the accusation in the presence of the SS leader. “While I was speaking, she positioned me behind her back to protect me. He reached for his pistol in fury, and it was not there,” Horvarth recalled. His wife had hidden the gun and Horvarth was able to escape.

Horvarth was later sent to Auschwitz. Her block was next to the railway tracks to the crematorium. “[One night] I could hear terrible screams,” she recalled. “What I saw was so terrible that I fell unconscious. They were throwing people who were still alive into the flames. Since this time I suffer from epileptic seizures.”

Eventually, after being moved to Ravensbrück concentration camp, Horvarth managed to escape and return home, but nothing was there. “No-one thought we would ever come back,” Horvarth recalled. “My entire possessions comprised a casserole dish and a spoon — and the courage to start a new life.” Horvarth died at the age of 33, on March 10, 1958, leaving behind her three children and partner Herr Gussak.

The official beginning of the Second World War in September 1939 meant the persecution expanded, as the German Reich marched on to invade Poland and France. Starting in early 1942, thousands of Roma who had been confined to ghettos in Poland were deported to Trebilinka and Chelmno concentration camps and murdered by gas. Later that year, Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, ordered most remaining Roma to be deported to occupied Poland from Germany.

In 1943, the Nazis created a specific section of the Auschwitz-Birkenhau camp designated the “Zigeunerlarger” or “Gypsy” camp. Around 23,000 Roma were deported to Auschwitz, of whom 21,000 were murdered in shootings and gas chambers.

The policy of genocide was made clear in a letter written by Himmler in 1944 stating that “the accomplished evacuation and isolation” of “Jews and Gypsies” meant that the initial directives against them were no longer necessary.

In part because so many Roma deaths went unrecorded, many families don’t know what happened to their relatives. Every week, the Wiener Holocaust Library’s researcher in charge of overlooking the ITS is contacted by people hoping to find out what happened to their loved ones.

Forced medical experiments

What did happen to them was often gruesome. In 1938, Dr. Robert Ritter, head of the Racial Hygiene Research Center at the Reich Bureau for Health, began a project with the aim of analyzing the “racial characteristics” of Roma.

Scientists would check their health, take their blood and measure their craniums. “They came up with spurious racist ideas about why Roma were inferior for genetic reasons,” says Warnock. This research provided the pseudo-scientific basis for the extermination and forced sterilization of thousands of Roma and Sinti.

The experiences of Theresia Reinhart, a Sinti woman who defied Nazi orders of forced sterilization and became pregnant, is featured in the Wiener Holocaust Library. Reinhart gave birth to twins, but her daughters, Rolanda and Rita, were taken away from her at birth by the Nazis. The twins were subjected to horrific medical experimentation. “Some of the Nazi scientists were interested in twin experiments, and so the poor babies were experimented on,” Warnock says. “One baby, Rolanda, died in the course of a medical experiment.”

Eventually, Reinhart’s daughter Rita was returned to her parents. After the war, mother and daughter set up a Sinti organization in Germany to campaign to raise awareness of what happened.

Margareta Kraus, who was deported to Auschwitz as a teenager with her family, is also featured in the exhibition. The only details Kraus divulged to journalist Reimer Gilsenbach in 1966 were that her parents both perished in Auschwitz and that she was then set to Ravenbrück camp where she worked as a slave laborer. But, using the ITS archive, Warnock found more detail about the ordeal Kraus went through.

“We found out that she’d been subject to forced medical experimentation in Auschwitz, which she hadn’t mentioned in her account. So we were able to learn more horrifying insight into her experiences,” Warnock says.

The fight for restitution

Across Europe since the post-war period, Roma have found it difficult to gain recognition of the scale of their persecution during WWII as well as make restitution claims. In part, this was because the persecution and murder of Roma was not prosecuted specifically at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials between 1945 and 1946 — and in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the experiences of Roma often went unacknowledged. German authorities denied that Roma were incarcerated in camps for racial reasons, arguing instead that they had been imprisoned because of an “a-social and criminal record.”

The experiences of Hans Braun, a German Sinti man, are illustrative of the difficulties in claiming restitution.

Braun, a forced laborer in a factory, was suspected of sabotage after accidentally breaking his machine in 1941. He went into hiding but was arrested and sent to Auschwitz; he was later transferred to Flossenbürg concentration camp in 1944. Braun first put in a claim for restitution in 1950. German police put criminal investigator Inspector Dalheim in charge of Braun’s restitution claim, with the aim of establishing, from the ITS, that Braun hadn’t been sent to Auschwitz or Flossenbürg concentration camps because of racial reasons, but because he was a criminal. Braun’s claim was denied. Experts like Warnock see this as an example of a concerted effort to discredit claims.

“This gives some insight into the difficulties that the Roma and Sinti faced immediately postwar with recognition and restitution claims,” says Warnock.

Braun later made a second restitution claim in 1956, which seems to have been successful, as he then applied for admission to Canada, where he started a family.

It wasn’t until 1982 that Germany officially recognized the persecution against Roma as a genocide based on race. France apologized for its collaboration in Nazi crimes against Roma and Sinti in 2016.

For Roma groups, it’s not enough.

The importance of remembering

Mainstream discussions about the Nazi persecution rarely address the Roma Holocaust.

Warnock argues that the continued marginalization of Roma in Europe means that it’s still a struggle to gain recognition for what happened. “For a group that is marginalized, it’s going to be hard to get their voices heard and represented,” she says.

Tania Gessi works for Roma Support Group, an organization that aims to do just this. “The Jewish people have been very explicit and verbal about their experience, and they really sought justice,” Gessi tells TIME. “For the Roma, it’s an entirely different story. For multiple reasons, they didn’t feel empowered to do that so now it’s really about giving them the voice that they didn’t have in the past to really highlight their experience… People are fighting for recognition of what happened in the past, but also what is happening now.”

Rabbi Jonathon Wittenberg, speaking at the opening of the Wiener Holocaust Museum’s exhibition, on Oct. 30, said: “I’m shocked at the isolation in which your communities are left with their legacy and this has to change, it has to end. We share together the responsibility of learning about this legacy. It affects those who were then and those who are now.”

Descendants of the persecuted Roma fear that if the Roma Holocaust experience is not remembered, history could repeat itself. “If you don’t educate the public about the Roma Holocaust, then future generations could do the same thing,” Abraham says.

Warnock agrees. “The awful events of the Nazi era very much reveal the danger of marginalizing and discriminating against minority groups, or groups who are less powerful in a society. They are very illustrative of the need to keep constantly vigilant in terms of prejudicial language and actions.”

In April of 2019, in Bulgaria, Krasimir Karakachanov, head of the Bulgarian National Movement, presented his “Roma integration strategy” to various ministers. It defines Roma people as “a-social Gypsies” and calls for a limit on the number of children Roma women can have by offering free abortions. The “strategy” is to be officially put on the government’s agenda, Karakachanov stated in July.

“The misconceptions that fueled the genocide are still around,” Abraham says. “The beast is there. It’s sleeping, but one day it could wake up again.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at [email protected]