In the fall of 2003, photographer David Burnett pitched a portrait shoot of career diplomat Joseph Wilson to U.S. News & World Report. That July, the New York Times had published an op-ed by Wilson that had significantly dented George W. Bush’s key argument for invading Iraq: that Saddam Hussein had tried to buy uranium from the west African nation of Niger to fuel his nuclear weapons program.

Wilson had written that some of this intelligence “was twisted to exaggerate the Iraqi threat,” an assertion that embarrassed the White House. It quickly retracted the claim that Bush had made in his State of the Union address earlier that year.

Shortly afterward, Wilson’s wife, Valerie Plame, was outed as a Central Intelligence Agency “operative on weapons of mass destruction.” The columnist Robert Novak, citing that two Bush administration officials had leaked Plame’s identity to him, wrote that Plame had suggested sending her husband to Africa. In an interview with TIME then, Wilson said that was “bullsh-t” and “a smear job.”

Wilson, who died on Sept. 27 at age 69, considered the leak to Novak an act of retribution. News coverage kicked into overdrive as investigations into one of the 21st century’s biggest national security scandals sought to unravel the chain of the disclosure: who had done what, at which levels of government, and why.

“I said, ‘You need to have me photograph him,’” Burnett, a cofounder of the Contact Press Images agency, recalls he told U.S. News that fall. The outlet agreed, and that same week he showed up to the family’s home in Washington, D.C. Plame hadn’t yet been photographed, and on this October day, that wasn’t Burnett’s intent.

“The door opens and there’s Valerie Plame in her bathrobe who’s down in the kitchen getting her little kids ready for school,” he tells TIME. “I was like, ‘You must be Valerie, hello.’ And she said ‘yeah, come on in. Joe’s right in here in the living room.’”

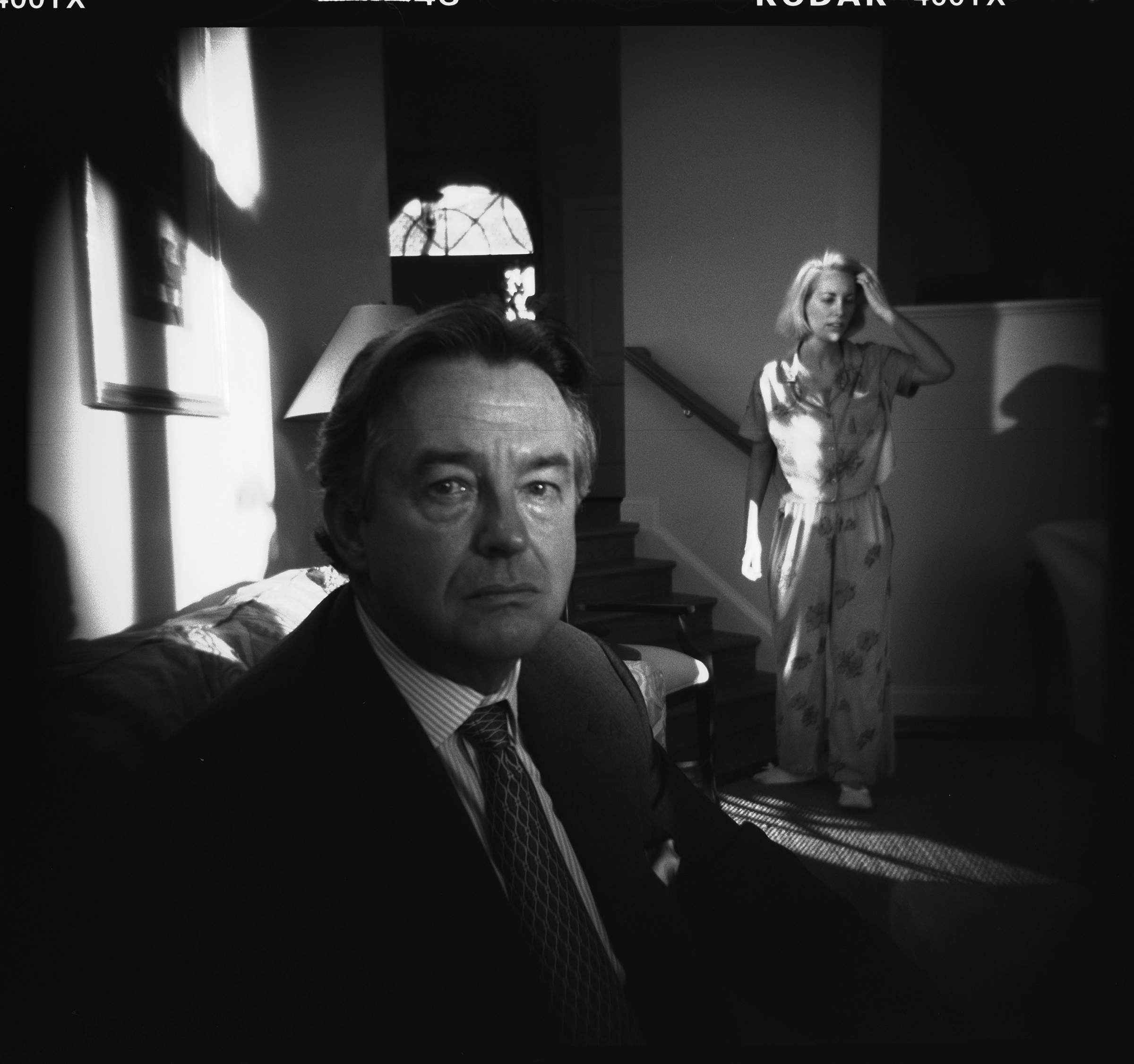

Bars of light streamed through the trees, hitting the window and wading into the room. Wilson sat on the couch as Burnett set up one of his cameras.

This was at the point when digital photography was “just grabbing hold of everything,” Burnett says. In what he describes as “this kind of allergic reaction” to the newer cameras, he had brought an old Speed Graphic 4×5, on a tripod, and a small, cheap, plastic Holga that required its film to be wound after each picture. It was crucial with a Holga to not over-wind or under-wind the film.

Once Burnett had Wilson in the frame and began shooting with the Holga, he paid closer attention to winding the film to the right number than to actually looking at what he was capturing. At one point, he remembers, “I shot four or five frames of him without really looking up.”

Afterward, he dropped the film off at the lab for processing. When Burnett returned around 4 p.m., he was stunned.

“I saw this astonishing vision of Joe sitting on the sofa, and Valerie had come in as if she was trying to remember something,” he says, “and then she just turned around and walked out.” A contact sheet of 11 images reveals only one that includes Plame.

“I have absolutely no memory of ever seeing her,” he says. “It was an accident, but sometimes accidents are the best pictures.”

Still, Burnett understood the sensitivities around publishing it. At one point, he called Wilson and talked it out. Wilson, who Burnett says wasn’t shown the image, outlined how releasing it then could be problematic for Plame, who still worked at the CIA. “That was the hardest thing,” Burnett admits, “knowing there was a story out there and holding on to the picture.”

He and Wilson made “a kind of gentleman’s agreement” that the picture wouldn’t be published while she was still at the agency. U.S. News ran a different one, slugged “ANGRY HUSBAND.” Plame did not return a request for comment.

In its January 2004 issue, Vanity Fair published a feature on Wilson and Plame with photographs by Jonas Karlsson. On the opening spread, Plame — styled with big sunglasses that shielded her face and a headscarf around her blond hair — is in the passenger seat of a convertible driven by Wilson. The White House is visible in the background. Wilson was quoted at the time saying the pictures, made a month after Burnett’s, “should not be able to identify her, or are not supposed to.”

Burnett saw the image and thought, “well, if she’s posing for Vanity Fair, I guess it’s ok,” and he and his agency looked to publish his image. U.S. News, by his account, was no longer interested. It later ran in TIME, in 2005, the year when Plame left the CIA and when Scooter Libby, then Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, was indicted.

This isn’t just a picture that Burnett could never imagine. He didn’t know it actually had happened.

That’s how it was, and is, with film. “It was a combination of you didn’t know what you had and you didn’t know what you had missed. And you kind of had your hopes up. But it was a world that was not at all a sure thing,” Burnett says. “There was something quite charming about the worrying in the pit of your stomach, that you didn’t know whether you had anything.”

Let alone a surprise.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at [email protected]